Sermons by Pastor Ashton Roberts

For those who find it helpful to read along while Pastor Ashton preaches.

Sermons by Pastor Ashton Roberts

I am reminded of a quote from The Office, when after a series of troubling events, Michael Scott says, “I’m not superstitious, but I am a little ‘stitious’.” Are you superstitious? I’d dare say that there are two main options. Either you are too rational, too enlightened and too educated to give in to such nonsense, or you are too beholden to tradition, or etiquette, or historical reenactment to open an umbrella indoors, or to walk under a ladder, to fail to say “bless you” when someone sneezes. Some of my favorite superstitions have to do with pocketknives. It is bad luck to close a knife you didn’t open. Stirring anything, like coffee or soup, with the blade of your pocketknife is bad luck. Cutting hot cornbread with a pocketknife is bad luck. Now with a little thought the origin of some of these can be easily explained. I can see a father handing a child a pocketknife to complete some task and asking that the knife be returned the way it was given in order to prevent the child from cutting themselves. And after seeing pocketknives being used for everything from gutting small game to picking the dirt from your fingernails you don’t have to be a microbiologist to see that sticking the blade in your food is a bad idea. But my favorite superstition has to do with the gifting of a knife. The common wisdom says that by gifting a knife you will soon sever the relationship. So, the work-around became that with the knife you also gift a coin. Then the recipient “pays” you the coin, and this “transaction” preserves the relationship. I love this tradition/superstition because of the love it implies. Not only have you implied your affection with the gift, but with the coin you have implied the hope that your relationship will continue. Now, I have to tell you, Gospel of Matthew is not my favorite. To me, the Good News that Matthew proclaims often feels a lot like getting a knife without the coin. It feels like the good news has come with an asterisk, warning “some assembly required.” The Gospel according to Ikea. Jesus tells us “I have come not to abolish the law but to fulfill [it].” Jesus tells us “Unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” Yikes. It feels like Jesus has given a gift that will soon sever our relationship with God and we’d better come up with enough righteousness to “pay” the giver of this gift before we run out of luck. It’s enough to make Luther roll over in his grave! If the righteousness that God requires of me is something I have to muster up out of my own heart and will then I am surely doomed, and this Gospel is no good news at all. Luckily, that’s not the Gospel at all. The gospel doesn’t start with the law. The gospel starts with God. God who IS Love. When we Lutherans talk about grace, we are talking about the way that Love behaves. We are talking about a God who is love and created the whole world out of that love. We are talking about a God who chose the people of Israel out of perfectly free love and said to them, “I will be your God and you will be my people.” Love precedes the Law. Grace came before the Law. Before God ever said “you shall not eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” God saw the universe God had created and said it was very good. Before God gave circumcision God called Abraham righteous. Before God gave the Ten Commandments, God led Israel out of Egypt. The law is not like the coin given with a knife. The law is not a transaction, not a means by which we ward off bad luck, not like that little hex wrench that comes with Ikea furniture. The Gospel of Matthew is the good news that we are already the people of God, and Jesus is showing us that Grace is how God’s people behave. The law is God’s proclamation “You are mine. Now act like it.” Jesus does not say “if you have faith you will be the salt of the earth. Jesus says “You ARE the salt of the earth. Act like it.” Jesus does not say “If you follow the ten commandments you will be the light of the world.” Jesus says, “You ARE the light of the world. Act like it.” The Good News of the Gospel is that we are God’s people ALREADY. And because we are God’s people we will love those God loves. The righteousness we enact will exceed that of the scribes and Pharisees because our righteousness is Christ’s own righteousness. In the gospel we have not been given a pocketknife and a coin; a token of God’s affection and the means to maintain the relationship. In the Gospel we are given the good news that we are already in the Kingdom of Heaven, that we are already righteous, that we are already God’s people. Now let us act like it. Amen.

As many of you may already know about me I grew up a fundamentalist. I was part of a tiny Appalachian Baptist tradition that believed the King James Version of the Bible was the only divinely inspired version of the Word of God. and therefore was “the only rule of faith and practice,” as the denomination’s charter stated. My faith was forged in the hellfire and brimstone preaching of this tradition and cooled in the soothing melodies of shaped note singing about the sweet by-and-by. My grandparents took me to church starting at age 2, letting me stay at their house every Saturday night, a tradition that only ended when I moved to college. My grandfather had this story about how he had come to the faith, miles underground in a coalmine in southwestern Virginia. One night, working in the deep darkness he cried out to God for salvation and it completely changed his life, and he would spend the rest of his life sharing Psalm 139:8 If I ascend up into heaven, thou art there: if I make my bed in hell, behold, thou art there. as if it had been written about his own life. Eventually, he met and married my grandmother, who came to the faith because of him. My grandfather even had his own radio show, where he would ‘testify’ live, on air each week. Many of the other folks in our church had these dramatic stories of instantaneous conversions where God had delivered them from a life of scandalous sin, and had now written their names in the Lamb’s book of life. When I was 7 years old, I understood that God loved me that Jesus had died for me, and that I wanted to go to heaven. So, when I was told that I needed to accept Jesus as my personal savior, of course, I did. Now, in this tradition, the next thing you do is you begin to learn to share your story, your testimony, as we called it. But I was seven. As you might imagine, my story couldn’t include that Jesus had delivered me from drinking or sleeping around, or gambling, or any of the other things that so many of the other testimonies had included. In fact, my realization that I needed a savior had come as something of a shock because it hadn’t ever occurred to me that I didn’t already have one. My faith had come from the witness of others, from their testimonies. From those whose life experiences had driven them to Jesus, whose conversions had literally saved their lives. But where was God in my own story? What good news did I have to share? In John’s gospel today, we see John’s experience of the Holy Spirit at Jesus’ baptism has led him to point to Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. It is John’s testimony, that Jesus is greater than himself, even offering a baptism greater than his own baptism, that Jesus is the Son of God, that compels his own disciples to leave John and follow Jesus. When Jesus sees John’s disciples following him he asks, “What are you looking for?” John had seen the Holy Spirit descend and confirm that Jesus is the Son of God. Maybe these disciples didn’t know what they were looking for. Maybe they were expecting something like the heavens rending, or voices booming, or a dove descending. We don’t know for sure what they did find, but whatever they found compelled Andrew to go and tell his brother that they had found the Messiah. The season of Epiphany is about recognizing God first in Jesus and then everywhere else. We see from John’s story and from Andrew’s story that God comes to us in the proclamation of the truth about Jesus. God is calling each of us to be preachers and prophets, to first recognize God in our own stories, and then go and tell these stories to others. But we cannot always identify God in our own stories. As I grew in my own faith, I realized that though I couldn’t point to a dramatic rescue or to an instantaneous conversion experience my testimony is that I cannot remember a time when I did not know Jesus. And, it wasn’t until I came into the Lutheran Church and began to hear the stories of folks mostly baptized as babies, who also couldn’t remember a time when they didn’t know Jesus, that I began to hear echoes of my own story. I found that God had been at work in my life the whole time. And I would never have known this without the testimony of others. This good news of God come near in Christ Has been passed from John the Baptist, to the disciples, to the early church, through 20 centuries of believers, into Appalachian coalmines, across AM radio waves, even through fundamentalist preachers. God is revealing Godself not only in the stories of others, but also in your own stories. God is continuing to write the story of the Gospel, in our hearts and lives, through our mouths and hands, calling us to testify to the God come near, first in Jesus, and then everywhere else, that you too may point to God in the flesh and echo John’s proclamation, Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. Amen.

What a busy few weeks it has been. I hope you found some rest to recuperate from the Christmas hustle and bustle. I am always grateful for vacation time, to relax and restore, to come back to work with renewed commitment and the energy to do all the things I have to do. But I imagine I am not alone in discovering that returning to work after a vacation is a bit surreal. It always takes a minute to remember the routines, to remember the passwords, to remember what it is I do on a Monday. My desk looks like my life did in December, cluttered with delayed tasks abandoned in the triage of looming deadlines, a stack of old bulletins waiting to be recycled, hastily written notes that I’m sure made sense when I wrote them, a cup of coffee I didn’t get the chance to finish. And sitting at that desk again I have a hard time trying to locate the renewed commitment and restored energy I thought I had found on vacation. I imagine that the return to the classroom, the shop, the office, the lab, feels much the same. What was that thing I was going to do? What was that change I was going to make? What was my resolution? When is my next vacation? I wonder too, if we don’t approach worship in much the same way. I hope that your time here in this place or the time you spend with us online is a source of renewal, of inspiration. I hope you find in this time together a sense of connection to God and to neighbor. I hope you remember who you are and whose you are and take with you the resolve to live a life of devotion and discipleship. But I also wonder if that inspiration, renewal, and devotion is harder to remember in the harsher reality of overflowing inboxes, looming deadlines, impatient clients, and traffic jams. It makes me wonder too if John the Baptist ever questioned his work. I wonder if he ever found it difficult to remember what drove him into the wilderness. I wonder if he questioned his message, his method, standing for hours in the murky waters of the Jordon, in wet camel hair with wrinkly toes and a belly full of locusts, baptizing repentant strangers. I can imagine his hope for the messiah had as much to do with finding some rest for himself as some rescue for his people. We hear echoes of his hope in his question, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” I need you, Jesus. I need a messiah to come and fix all this. I need a rescuer to come and save us from Rome, from ourselves. I need to be reminded that this work is not in vain, that this work is accomplishing something larger than me. I need to know that my sacrifice is seen, is valued, is effective. I need to be baptized by you. Why do you need to be baptized? Theologians, pastors, preachers, and parishioners have been repeating John’s question since he asked it. If this Jesus is God why does he come for a baptism of repentance? Of what does Jesus need to repent? But I think this is the wrong question. The church has spent some 20 centuries defining, articulating, and proclaiming one baptism for the forgiveness of sin. We speak of a rite of initiation, of inclusion. Paul speaks of our old selves being buried with Christ and raised with him to new life. We speak so much and so often of what baptism is and does that we haven’t seen the forest for the trees. Baptism is a rite on initiation. Baptism does forgive our sins. Baptism does unite us to Christ. But this day to remember the Baptism of Jesus, set here in this season inaugurated by the Feast of the Epiphany, invites us to see something less familiar to us in the rite of baptism. This season after Epiphany is about encountering the mystery of incarnation, about contemplating the union of God and matter, the manifestation of God with us in the person of Jesus, the Christ. Baptism is about more than initiation or inclusion, forgiveness or religious identity. Our baptism is the beginning of a new way of showing up in the world, a new way of seeing and encountering the world. Jesus was baptized by John in the Jordon to give us the gift of baptism, a sacred mystery that reveals the sacred mystery at the heart of the universe— the whole of creation is a sacrament. The whole world is a sacrament, the union of matter and God’s very self. And in this sacramental universe we are each priests, ministers of word and work. No matter your vocation, no matter your occupation, you are the steward of a sacred mystery in which God transforms your work into a means of grace. Your scrubs, lab coat, uniform; your nametag, backpack, briefcase; your sport coat, pants suit, apron are all sacred vestments. Your desk, work bench, hospital bed; your countertop, stovetop, laptop; your changing table, kitchen table, conference table; each are a sacred altar where you pour out yourself as an offering and receive back nourishment in return. We do not come to worship, to the font or the altar, to find this sacred mystery in the only place that it exists. We come to worship, to the font and the altar, to learn to see this sacred mystery everywhere that it exists. We should learn from these sacraments to see that God in Christ, revealed in the humble majesty of his birth, proclaimed from heaven in his baptism, is not a singularity in the story of the cosmos, but a particularity which exposes the deeper truth. The incarnation is not limited to Jesus. The incarnation is exposed in Jesus. This is the Epiphany, the revelation of God in Christ, after which we begin to see the God in all things. The whole cosmos is filled with God. All creation emanates from God’s very being, and is destined to return to this source. This is what we mean by salvation. Baptism is the proclamation that this human, this sinner, this mortal, is also divine, a saint, immortal. Creation is filled with the life and love of God. Your life is filled with the life and love of God. Your work is an extension of this Creation, and your work too is filled with the life and love of God. We, like John the Baptist, encounter the Christ in every patient, client, customer; in every student, parent, volunteer; in every spouse, child, neighbor. We, like John, must approach our work as a sacred honor, a humble privilege of service to God’s very self. This does not mean that Mondays won’t suck, that customers won’t complain, that inboxes won’t overwhelm us, that babies won’t cry, that we won’t get sick and tired of standing in our private Jordons wishing to be rescued. It will mean that we begin to see the sacrifice as unto God, as part of a larger sacred mystery as a holy privilege of humble service in a world overflowing with the life and love of God. Amen.

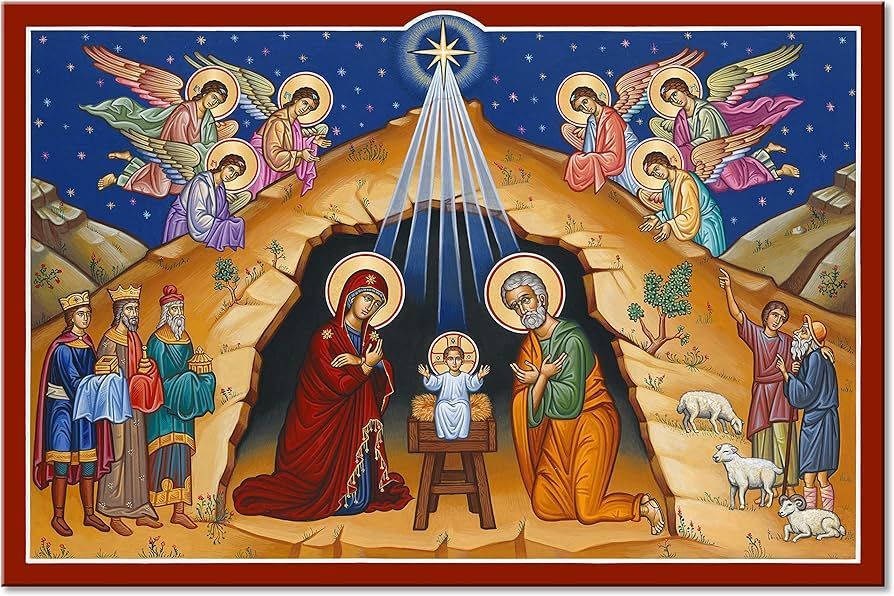

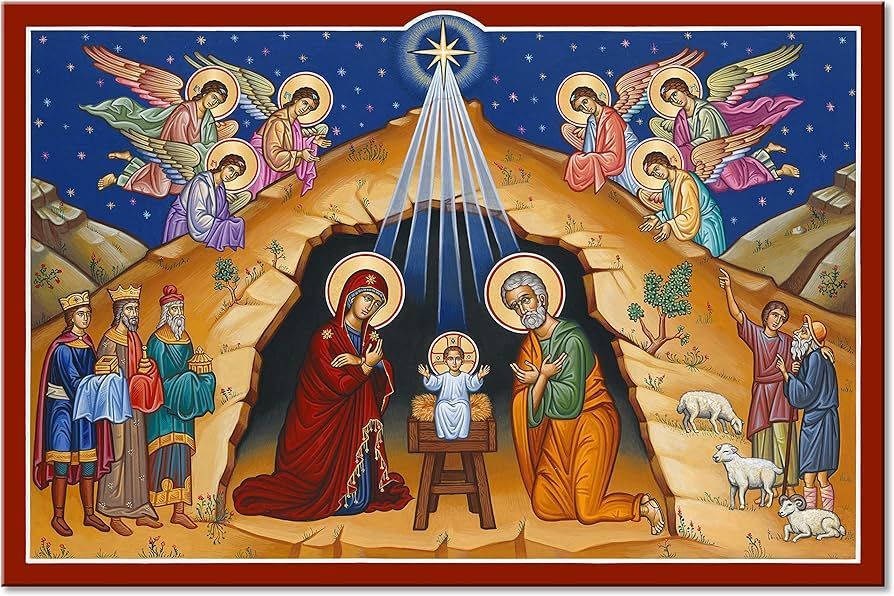

Like most folks, I suspect, I love Christmas carols. They stick in my head Long after the tree is gone, And the lights are put away. I would dare say that most of us could even sing the first verses of most Christmas carols by heart. 100% off-book. Think about it, “Joy to the World,” “Silent Night,” “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” “The First Noel,” “It Came upon a Midnight Clear.” But the real meat of these carols is in the second, or even third verse. Take for instance, “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” We could all sing Yet in thy dark streets shineth The everlasting light, The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight. But do we pray O holy Child of Mary Descend to us, we pray. Cast out our sin And enter in, Be born in us today? The birth of this Christ child is not some abstract theological concept with no bearing on our reality. Nor is this baby the object of mere sentimentality. This child’s birth is good news to shepherds Working the third shift And living in a field To whom It came upon a midnight clear, That glorious song of old… “Peace on the earth, Good will to all, From heaven’s all gracious king.” But you don’t have to work the third shift to identify with the next verse: And you, beneath life’s crushing load, Whose forms are bending low, Who toil along the climbing way With painful steps and slow; Look now, for glad and golden hours come swiftly on the wing; oh, rest beside the weary road and hear the angels sing. And in this child, whom the herald angels sing we, Veiled in flesh the Godhead see! Hail, incarnate Deity!... Mild he lays his glory by, Born that we no more may die, Born to raise each child of earth Born to give them second birth. Our hope is that this God veiled in flesh This incarnate deity Is Emmanuel. God with us. God for us. The God of shepherds Who lays his glory by To shine in dark streets, Pleased as a man with us to dwell. Epiphany is the second verse of Christmas. Epiphany is where the story gets complicated. Epiphany is where we realize just how vulnerable God is in the form of a baby, in early first century Palestine, under the reign of a murderous tyrant, bent on keeping power at all costs. The epiphany is that God is vulnerable because God is love. In this Love incarnate, we find that grace is the very nature of the Universe, because grace is the word we use to describe the way love behaves toward the beloved. This is the mystery we heard about in Ephesians, the light we heard about in Isaiah, and the guiding star of those wise men. Christ Jesus, God in the flesh, Love in a body, revealed to the whole world. Many of us could sing O holy night, The stars are brightly shining, It is the night of our dear Savior’s birth. As we go from here, Into a world divided, awash in pain, and on the brink of war We must remember that Truly he taught us to love one another, His law is love and his gospel is peace Chains shall he break, For the slave is our brother, And in his name, All oppression shall cease. His law is love and his gospel is peace! As the songs of angels cease, as the babe in the manger becomes the toddler on Mary’s knee, as the wise men take another road home, we begin to live into the second verse of the incarnation. The verse that tells us that the Almighty is also the all-vulnerable. That God has come among us, to live and love, to suffer and die alongside us. To live and love to suffer and die, not instead of us but in us, and through us. God’s radical solidarity with the whole of creation in Jesus Christ is the Epiphany. And this radical solidarity is the calling of the whole church. Where there is pain, where there is suffering, where there is oppression, we are sent not only to proclaim good news but to embody the law of love and the gospel of peace. May the Epiphany continue in each of us! Amen.

What I have learned in these past few years of living in Atlanta is that the traffic is really not as bad as it is usually made out to be. It is the driving that is terrible. Nearly every trip I make feels like some kind of road hazard simulation, wherein the objective is to arrive at your destination alive, the car in one piece, on time, and in obedience to the law. Often, I am forced to sacrifice at least one of these objectives to get where I am going and home again. Since I arrived here alive, in an intact vehicle, and on time, I’ll let you guess which objective I most often sacrifice. This seeming simulation is not gridlock, all of us stuck on the freeway, inching along, hour by hour. It is more like an obstacle course of pedestrians, racecars, school busses, debris from accidents, roadkill from armadillos to contorted deer, out of state tags, and distracted drivers. Almost every day, I have to maneuver around someone going 12 miles below the speed limit, and as I pass, I can see the tell-tale chin to chest posture of someone looking at their phone. Or they’re navigating the GPS on their mounted device. I have seen folks putting on makeup at 32 mph in the left lane. Once on 285, I saw a man reading a full-size newspaper with both hands in a car that I am almost certain does not have a self-driving feature. I’ve seen folks eating entire meals, vaping mushroom clouds out the driver’s window, changing shirts, holding a lapful of small dogs— or children— and I’m sure each of you could add to this list of circus tricks. Father Richard Rohr says that how we do anything is how we do everything. That is, if we take just a moment to consider our driving, we can see that we are driving like we are living our whole lives— distracted, in a hurry, anxious, and dangerously inconsiderate. We are all in a hurry, and none of us are used to doing one thing at a time. We have been conditioned by our culture, by our employers, by social media videos of life hacks, to believe that we should be maximally efficient, that we should be able to walk and chew gum and do calculus in our heads, all at the same time. All of the preparations leading up to this holiday only add to a never-ending list of responsibilities, expectations, deadlines, and outcomes we have to meet. It’s no wonder we can’t drive undistracted. And it’s no wonder that we are so resistant to the idea of prayer. Who has time? Who can be still? Even if I sit still, my mind is racing, filled with to-do lists and disquiet, with memories of that time when the guy in the drive thru said, “Come again!” and you said, “You too!” You can’t stop feeling kind of offended when that lady at work saw your new shirt and said, “What a unique color.” What’s that supposed to mean? You can’t stop feeling the mixture of anger and sadness that only grief can bring. We think of prayer, contemplation, mindfulness, as something beyond us, something for monks and mystics not parents and people with day jobs. Multitasking is the opposite of contemplation. But I think it is also the beginning. Near the end of our gospel reading is a curious phrase. “Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.” Now, Mary, while traveling, has just given birth in a barn, with a feeding trough for a crib. She’s been visited by a band of uninvited— and likely unwashed— shepherds who were directed to this barn by a company of the heavenly host. Road-weary and child-birth exhausted Mary receives the shepherds’ story, treasuring and pondering it “in her heart.” There is another form of contemplation, meditation, prayer, for us working stiffs that we aren’t often taught. Mary is the mother of an infant. Do you really think she has the time for a 20-minute meditation practice twice per day? No. Nor could most of us carve out such time in our busy days to sit silently and meditate. But Mary can be our model for a new kind of prayer. ************************ St. Julian of Norwich is often depicted with a hazelnut in one hand. St. Julian saw a truth about the whole universe contained in this tiny hazelnut. She wrote, “In this little thing I saw three properties. The first is that God made it. The second that God loves it. And the third, that God keeps it.” In the focused attention of St. Julian she became aware of a truth beneath, behind, and beyond the hazelnut, namely that God made, loves, and holds together the whole universe. This is the same truth proclaimed to Mary by angels and shepherds which she treasured and pondered in her heart. But instead of a hazelnut, she had this baby, wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger. When we are multitasking like a one-man band we cannot focus our attention on just one thing. But if we can focus on just one thing we too might find the love of God hidden beneath, behind, and beyond this one thing. We, like Mary, are given this baby to focus our attention this Christmas. We are given this hour, this worship service, to treasure these words and ponder them in our hearts. We are given this bit of bread and this sip of wine that focusing our attention on Body and Blood of Jesus we too might find that we are made by God, loved by God, and kept by God, just like everything else in the universe. Tonight, tomorrow, and over the days to come, from time to time, take just a moment to focus your attention on the thing at hand, your work in the moment. As you pack away your decorations, maybe this year, keep out the manger and the baby Jesus. Let this baby be a reminder to focus your attention in the moment. Over time, you will begin to see as Mary and St. Julian saw, the love of God hidden beneath, behind, and beyond this moment, this work, this object. This seeing will transform your whole life. And it might even make you a better driver. Amen.

In liturgical year A, our gospel readings will be set primarily in the Gospel of Matthew. Each of the four gospels provides a unique perspective on the message, ministry, and person of Jesus. Historically, the Gospels are each depicted in art with symbols that represent the tone of the book. Mark, probably the first of the four, is short and action packed, and is depicted as a winged lion. Luke, written by a physician, and the most complex, is depicted as a winged ox, a beast of burden, for all the work this gospel is doing. John’s gospel, written last, is written once the church has had ample opportunity to grapple with who this Jesus is, and because they know him to be God in the flesh, one step ahead of everyone else. John’s gospel is depicted as an eagle, an image of Jesus’ soaring rhetoric and transcendence. But the gospel of Matthew, written sometime between Mark and Luke, is about Emmanuel, God with us. For Matthew, Jesus is a prophet, a priest, a king. Jesus is the new Moses, the new Elijah. Matthew’s gospel begins with the promise that this child born to Mary is Emmanuel, God with us, and ends with Jesus’ promise, “I am with you always, to the end of the age.” The Gospel of Matthew is depicted as a person. For Matthew, this image of God— born of the flesh, born of a woman, born into the care of Joseph— this Jesus is Emmanuel, God with us in the flesh. But Joseph didn’t have the benefit of 2000 years of interpretation and art history to help him understand that the news he had received about Mary’s pregnancy was anything more than an insult, a slap in the face, an assault on his manhood, on his dignity. Joseph was a righteous man, by all accounts. He was perfectly within his rights under the Law, to send her away, to break the engagement, which actually required a divorce, even though they were not yet married. He would also have been within his rights to expose her, to reveal her obvious treachery, her infidelity, to condemn her. But because he is a man of righteous character, and possibly because he loved her, he chooses to simply sidestep the issue, after all, this clearly isn’t his problem. This was done to him. But rather than open the both of them to public shame, he will send her away quietly, and he will return to his normal life. And who could blame him. Why should he be responsible for someone else’s child? Someone else’s family? There are many in our own lives we would be content to “put away quietly,” to wash our hands of, to absolve ourselves of any responsibility for. It is easy to think, “I cannot cure poverty. I do well to make my own ends meet. Surely, God does not expect me to do more for others that I am able to do for myself.” Maybe our thinking sounds more like “I have worked my tail off to get where I am. Those who don’t have what I do couldn’t have worked as hard as I have, so let them work for it like I did.” “I don’t mind people coming here to escape violence in their home countries, but they should do it legally. We can’t help everybody!” Maybe we’ve been tempted to throw up our hands give up on the idea of climate change, or social justice, or even just loving our neighbor because the difference we’d make alone will never solve the problem. Or maybe we’re ready to walk away from Christianity altogether, because it seems like it’s more obsessed with self-preservation than living the example of Jesus. Whatever it is, you are not alone in feeling crushed by the weight of something larger than you, larger than you can change alone, larger than you can solve alone. And like Joseph, there is nothing to stop us from leaving, nothing and no one to prevent us from putting away quietly all the things we’d rather not be responsible for. When Joseph has made up his mind to use the right he has to walk away, God comes to Joseph in a dream. God comes and confronts Joseph with the opportunity to go beyond the letter of the law to live by the root of the law: Love. God calls Joseph to do what God is doing. God too is righteous. God too could have looked at the human race in our neediness and wantonness, and God could have walked away. God could have killed Adam and Eve in the Garden. God could have killed Noah in the flood. God could have let the children of Israel remain in slavery in Egypt, or killed them with starvation and thirst when they complained about their freedom. God could have put away Israel because of David’s sin, could have destroyed the people under the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, the Romans. But God didn’t. God loved anyway. God left the garden too. God gave the rainbow to Noah as a promise that God would overlook human sin. God wandered the desert in a tent and received no sacrifices when the Israelites ate only manna. God tied God’s honor and glory to the honor and glory of David. And when Solomon’s temple was destroyed, God went into exile, too. And now, God has come to Joseph in a dream. God has come to Joseph in the life and faithfulness of Mary. God is coming in the flesh and bones of Jesus. And beloved, God is still coming in flesh and bone. Matthew’s gospel is represented by a human face to remind us to look for God hiding behind human faces. God is with us in those we would prefer to put away quietly. God is with us in solidarity with the human condition, choosing our lot as God’s own, making our needs God’s needs. Making our suffering God’s suffering. Making our joy God’s joy. This is love; choosing to live in solidarity with another until their problems are our problems, their joys are our joys, their lives are our lives. Joseph shows us what it is to love, what it is to live in solidarity, by hearing and trusting the call of God to take Mary as his wife and Jesus as his own son. We too have the opportunity to live in this solidarity, seeing God in the human faces we encounter in our work, in our world, in our homes, and even in the mirror. God is coming in the flesh. O come to us, abide with us, our God, Emmanuel!! Amen.