Welcome

All Saints Lutheran Church (ELCA)

Lilburn, GA

Sunday Mornings, 10 AM

Worship, Fellowship, Purpose

We are a welcoming community called by God to live out the message of Christ in love and service to all people.

"[The saints] devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers." Acts 2:42

Service Times

Sunday Worship: 10:00 AM

We offer worship with Communion in-person with masks optional. The service is also cast on Facebook Live and over Zoom for those who prefer to remain remote. See Worship Resources below for bulletins, Lifeline newsletters, sermon texts, Zoom link, and FaceBook Live link for each Sunday.

Follow Us

Keep up with our latest news

Recent Sermons

What a busy few weeks it has been. I hope you found some rest to recuperate from the Christmas hustle and bustle. I am always grateful for vacation time, to relax and restore, to come back to work with renewed commitment and the energy to do all the things I have to do. But I imagine I am not alone in discovering that returning to work after a vacation is a bit surreal. It always takes a minute to remember the routines, to remember the passwords, to remember what it is I do on a Monday. My desk looks like my life did in December, cluttered with delayed tasks abandoned in the triage of looming deadlines, a stack of old bulletins waiting to be recycled, hastily written notes that I’m sure made sense when I wrote them, a cup of coffee I didn’t get the chance to finish. And sitting at that desk again I have a hard time trying to locate the renewed commitment and restored energy I thought I had found on vacation. I imagine that the return to the classroom, the shop, the office, the lab, feels much the same. What was that thing I was going to do? What was that change I was going to make? What was my resolution? When is my next vacation? I wonder too, if we don’t approach worship in much the same way. I hope that your time here in this place or the time you spend with us online is a source of renewal, of inspiration. I hope you find in this time together a sense of connection to God and to neighbor. I hope you remember who you are and whose you are and take with you the resolve to live a life of devotion and discipleship. But I also wonder if that inspiration, renewal, and devotion is harder to remember in the harsher reality of overflowing inboxes, looming deadlines, impatient clients, and traffic jams. It makes me wonder too if John the Baptist ever questioned his work. I wonder if he ever found it difficult to remember what drove him into the wilderness. I wonder if he questioned his message, his method, standing for hours in the murky waters of the Jordon, in wet camel hair with wrinkly toes and a belly full of locusts, baptizing repentant strangers. I can imagine his hope for the messiah had as much to do with finding some rest for himself as some rescue for his people. We hear echoes of his hope in his question, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” I need you, Jesus. I need a messiah to come and fix all this. I need a rescuer to come and save us from Rome, from ourselves. I need to be reminded that this work is not in vain, that this work is accomplishing something larger than me. I need to know that my sacrifice is seen, is valued, is effective. I need to be baptized by you. Why do you need to be baptized? Theologians, pastors, preachers, and parishioners have been repeating John’s question since he asked it. If this Jesus is God why does he come for a baptism of repentance? Of what does Jesus need to repent? But I think this is the wrong question. The church has spent some 20 centuries defining, articulating, and proclaiming one baptism for the forgiveness of sin. We speak of a rite of initiation, of inclusion. Paul speaks of our old selves being buried with Christ and raised with him to new life. We speak so much and so often of what baptism is and does that we haven’t seen the forest for the trees. Baptism is a rite on initiation. Baptism does forgive our sins. Baptism does unite us to Christ. But this day to remember the Baptism of Jesus, set here in this season inaugurated by the Feast of the Epiphany, invites us to see something less familiar to us in the rite of baptism. This season after Epiphany is about encountering the mystery of incarnation, about contemplating the union of God and matter, the manifestation of God with us in the person of Jesus, the Christ. Baptism is about more than initiation or inclusion, forgiveness or religious identity. Our baptism is the beginning of a new way of showing up in the world, a new way of seeing and encountering the world. Jesus was baptized by John in the Jordon to give us the gift of baptism, a sacred mystery that reveals the sacred mystery at the heart of the universe— the whole of creation is a sacrament. The whole world is a sacrament, the union of matter and God’s very self. And in this sacramental universe we are each priests, ministers of word and work. No matter your vocation, no matter your occupation, you are the steward of a sacred mystery in which God transforms your work into a means of grace. Your scrubs, lab coat, uniform; your nametag, backpack, briefcase; your sport coat, pants suit, apron are all sacred vestments. Your desk, work bench, hospital bed; your countertop, stovetop, laptop; your changing table, kitchen table, conference table; each are a sacred altar where you pour out yourself as an offering and receive back nourishment in return. We do not come to worship, to the font or the altar, to find this sacred mystery in the only place that it exists. We come to worship, to the font and the altar, to learn to see this sacred mystery everywhere that it exists. We should learn from these sacraments to see that God in Christ, revealed in the humble majesty of his birth, proclaimed from heaven in his baptism, is not a singularity in the story of the cosmos, but a particularity which exposes the deeper truth. The incarnation is not limited to Jesus. The incarnation is exposed in Jesus. This is the Epiphany, the revelation of God in Christ, after which we begin to see the God in all things. The whole cosmos is filled with God. All creation emanates from God’s very being, and is destined to return to this source. This is what we mean by salvation. Baptism is the proclamation that this human, this sinner, this mortal, is also divine, a saint, immortal. Creation is filled with the life and love of God. Your life is filled with the life and love of God. Your work is an extension of this Creation, and your work too is filled with the life and love of God. We, like John the Baptist, encounter the Christ in every patient, client, customer; in every student, parent, volunteer; in every spouse, child, neighbor. We, like John, must approach our work as a sacred honor, a humble privilege of service to God’s very self. This does not mean that Mondays won’t suck, that customers won’t complain, that inboxes won’t overwhelm us, that babies won’t cry, that we won’t get sick and tired of standing in our private Jordons wishing to be rescued. It will mean that we begin to see the sacrifice as unto God, as part of a larger sacred mystery as a holy privilege of humble service in a world overflowing with the life and love of God. Amen.

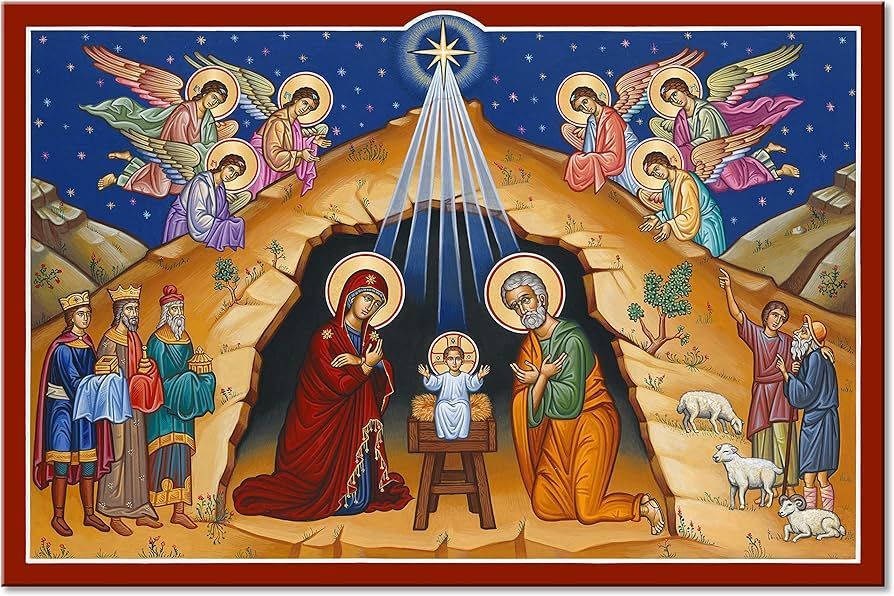

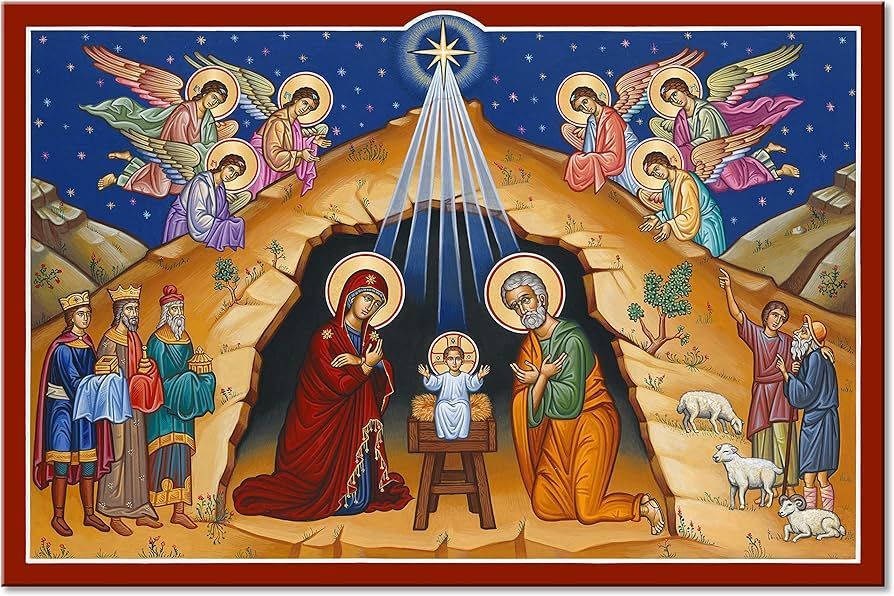

Like most folks, I suspect, I love Christmas carols. They stick in my head Long after the tree is gone, And the lights are put away. I would dare say that most of us could even sing the first verses of most Christmas carols by heart. 100% off-book. Think about it, “Joy to the World,” “Silent Night,” “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” “The First Noel,” “It Came upon a Midnight Clear.” But the real meat of these carols is in the second, or even third verse. Take for instance, “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” We could all sing Yet in thy dark streets shineth The everlasting light, The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight. But do we pray O holy Child of Mary Descend to us, we pray. Cast out our sin And enter in, Be born in us today? The birth of this Christ child is not some abstract theological concept with no bearing on our reality. Nor is this baby the object of mere sentimentality. This child’s birth is good news to shepherds Working the third shift And living in a field To whom It came upon a midnight clear, That glorious song of old… “Peace on the earth, Good will to all, From heaven’s all gracious king.” But you don’t have to work the third shift to identify with the next verse: And you, beneath life’s crushing load, Whose forms are bending low, Who toil along the climbing way With painful steps and slow; Look now, for glad and golden hours come swiftly on the wing; oh, rest beside the weary road and hear the angels sing. And in this child, whom the herald angels sing we, Veiled in flesh the Godhead see! Hail, incarnate Deity!... Mild he lays his glory by, Born that we no more may die, Born to raise each child of earth Born to give them second birth. Our hope is that this God veiled in flesh This incarnate deity Is Emmanuel. God with us. God for us. The God of shepherds Who lays his glory by To shine in dark streets, Pleased as a man with us to dwell. Epiphany is the second verse of Christmas. Epiphany is where the story gets complicated. Epiphany is where we realize just how vulnerable God is in the form of a baby, in early first century Palestine, under the reign of a murderous tyrant, bent on keeping power at all costs. The epiphany is that God is vulnerable because God is love. In this Love incarnate, we find that grace is the very nature of the Universe, because grace is the word we use to describe the way love behaves toward the beloved. This is the mystery we heard about in Ephesians, the light we heard about in Isaiah, and the guiding star of those wise men. Christ Jesus, God in the flesh, Love in a body, revealed to the whole world. Many of us could sing O holy night, The stars are brightly shining, It is the night of our dear Savior’s birth. As we go from here, Into a world divided, awash in pain, and on the brink of war We must remember that Truly he taught us to love one another, His law is love and his gospel is peace Chains shall he break, For the slave is our brother, And in his name, All oppression shall cease. His law is love and his gospel is peace! As the songs of angels cease, as the babe in the manger becomes the toddler on Mary’s knee, as the wise men take another road home, we begin to live into the second verse of the incarnation. The verse that tells us that the Almighty is also the all-vulnerable. That God has come among us, to live and love, to suffer and die alongside us. To live and love to suffer and die, not instead of us but in us, and through us. God’s radical solidarity with the whole of creation in Jesus Christ is the Epiphany. And this radical solidarity is the calling of the whole church. Where there is pain, where there is suffering, where there is oppression, we are sent not only to proclaim good news but to embody the law of love and the gospel of peace. May the Epiphany continue in each of us! Amen.

What I have learned in these past few years of living in Atlanta is that the traffic is really not as bad as it is usually made out to be. It is the driving that is terrible. Nearly every trip I make feels like some kind of road hazard simulation, wherein the objective is to arrive at your destination alive, the car in one piece, on time, and in obedience to the law. Often, I am forced to sacrifice at least one of these objectives to get where I am going and home again. Since I arrived here alive, in an intact vehicle, and on time, I’ll let you guess which objective I most often sacrifice. This seeming simulation is not gridlock, all of us stuck on the freeway, inching along, hour by hour. It is more like an obstacle course of pedestrians, racecars, school busses, debris from accidents, roadkill from armadillos to contorted deer, out of state tags, and distracted drivers. Almost every day, I have to maneuver around someone going 12 miles below the speed limit, and as I pass, I can see the tell-tale chin to chest posture of someone looking at their phone. Or they’re navigating the GPS on their mounted device. I have seen folks putting on makeup at 32 mph in the left lane. Once on 285, I saw a man reading a full-size newspaper with both hands in a car that I am almost certain does not have a self-driving feature. I’ve seen folks eating entire meals, vaping mushroom clouds out the driver’s window, changing shirts, holding a lapful of small dogs— or children— and I’m sure each of you could add to this list of circus tricks. Father Richard Rohr says that how we do anything is how we do everything. That is, if we take just a moment to consider our driving, we can see that we are driving like we are living our whole lives— distracted, in a hurry, anxious, and dangerously inconsiderate. We are all in a hurry, and none of us are used to doing one thing at a time. We have been conditioned by our culture, by our employers, by social media videos of life hacks, to believe that we should be maximally efficient, that we should be able to walk and chew gum and do calculus in our heads, all at the same time. All of the preparations leading up to this holiday only add to a never-ending list of responsibilities, expectations, deadlines, and outcomes we have to meet. It’s no wonder we can’t drive undistracted. And it’s no wonder that we are so resistant to the idea of prayer. Who has time? Who can be still? Even if I sit still, my mind is racing, filled with to-do lists and disquiet, with memories of that time when the guy in the drive thru said, “Come again!” and you said, “You too!” You can’t stop feeling kind of offended when that lady at work saw your new shirt and said, “What a unique color.” What’s that supposed to mean? You can’t stop feeling the mixture of anger and sadness that only grief can bring. We think of prayer, contemplation, mindfulness, as something beyond us, something for monks and mystics not parents and people with day jobs. Multitasking is the opposite of contemplation. But I think it is also the beginning. Near the end of our gospel reading is a curious phrase. “Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.” Now, Mary, while traveling, has just given birth in a barn, with a feeding trough for a crib. She’s been visited by a band of uninvited— and likely unwashed— shepherds who were directed to this barn by a company of the heavenly host. Road-weary and child-birth exhausted Mary receives the shepherds’ story, treasuring and pondering it “in her heart.” There is another form of contemplation, meditation, prayer, for us working stiffs that we aren’t often taught. Mary is the mother of an infant. Do you really think she has the time for a 20-minute meditation practice twice per day? No. Nor could most of us carve out such time in our busy days to sit silently and meditate. But Mary can be our model for a new kind of prayer. ************************ St. Julian of Norwich is often depicted with a hazelnut in one hand. St. Julian saw a truth about the whole universe contained in this tiny hazelnut. She wrote, “In this little thing I saw three properties. The first is that God made it. The second that God loves it. And the third, that God keeps it.” In the focused attention of St. Julian she became aware of a truth beneath, behind, and beyond the hazelnut, namely that God made, loves, and holds together the whole universe. This is the same truth proclaimed to Mary by angels and shepherds which she treasured and pondered in her heart. But instead of a hazelnut, she had this baby, wrapped in bands of cloth and lying in a manger. When we are multitasking like a one-man band we cannot focus our attention on just one thing. But if we can focus on just one thing we too might find the love of God hidden beneath, behind, and beyond this one thing. We, like Mary, are given this baby to focus our attention this Christmas. We are given this hour, this worship service, to treasure these words and ponder them in our hearts. We are given this bit of bread and this sip of wine that focusing our attention on Body and Blood of Jesus we too might find that we are made by God, loved by God, and kept by God, just like everything else in the universe. Tonight, tomorrow, and over the days to come, from time to time, take just a moment to focus your attention on the thing at hand, your work in the moment. As you pack away your decorations, maybe this year, keep out the manger and the baby Jesus. Let this baby be a reminder to focus your attention in the moment. Over time, you will begin to see as Mary and St. Julian saw, the love of God hidden beneath, behind, and beyond this moment, this work, this object. This seeing will transform your whole life. And it might even make you a better driver. Amen.

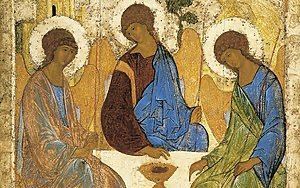

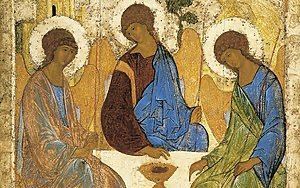

In liturgical year A, our gospel readings will be set primarily in the Gospel of Matthew. Each of the four gospels provides a unique perspective on the message, ministry, and person of Jesus. Historically, the Gospels are each depicted in art with symbols that represent the tone of the book. Mark, probably the first of the four, is short and action packed, and is depicted as a winged lion. Luke, written by a physician, and the most complex, is depicted as a winged ox, a beast of burden, for all the work this gospel is doing. John’s gospel, written last, is written once the church has had ample opportunity to grapple with who this Jesus is, and because they know him to be God in the flesh, one step ahead of everyone else. John’s gospel is depicted as an eagle, an image of Jesus’ soaring rhetoric and transcendence. But the gospel of Matthew, written sometime between Mark and Luke, is about Emmanuel, God with us. For Matthew, Jesus is a prophet, a priest, a king. Jesus is the new Moses, the new Elijah. Matthew’s gospel begins with the promise that this child born to Mary is Emmanuel, God with us, and ends with Jesus’ promise, “I am with you always, to the end of the age.” The Gospel of Matthew is depicted as a person. For Matthew, this image of God— born of the flesh, born of a woman, born into the care of Joseph— this Jesus is Emmanuel, God with us in the flesh. But Joseph didn’t have the benefit of 2000 years of interpretation and art history to help him understand that the news he had received about Mary’s pregnancy was anything more than an insult, a slap in the face, an assault on his manhood, on his dignity. Joseph was a righteous man, by all accounts. He was perfectly within his rights under the Law, to send her away, to break the engagement, which actually required a divorce, even though they were not yet married. He would also have been within his rights to expose her, to reveal her obvious treachery, her infidelity, to condemn her. But because he is a man of righteous character, and possibly because he loved her, he chooses to simply sidestep the issue, after all, this clearly isn’t his problem. This was done to him. But rather than open the both of them to public shame, he will send her away quietly, and he will return to his normal life. And who could blame him. Why should he be responsible for someone else’s child? Someone else’s family? There are many in our own lives we would be content to “put away quietly,” to wash our hands of, to absolve ourselves of any responsibility for. It is easy to think, “I cannot cure poverty. I do well to make my own ends meet. Surely, God does not expect me to do more for others that I am able to do for myself.” Maybe our thinking sounds more like “I have worked my tail off to get where I am. Those who don’t have what I do couldn’t have worked as hard as I have, so let them work for it like I did.” “I don’t mind people coming here to escape violence in their home countries, but they should do it legally. We can’t help everybody!” Maybe we’ve been tempted to throw up our hands give up on the idea of climate change, or social justice, or even just loving our neighbor because the difference we’d make alone will never solve the problem. Or maybe we’re ready to walk away from Christianity altogether, because it seems like it’s more obsessed with self-preservation than living the example of Jesus. Whatever it is, you are not alone in feeling crushed by the weight of something larger than you, larger than you can change alone, larger than you can solve alone. And like Joseph, there is nothing to stop us from leaving, nothing and no one to prevent us from putting away quietly all the things we’d rather not be responsible for. When Joseph has made up his mind to use the right he has to walk away, God comes to Joseph in a dream. God comes and confronts Joseph with the opportunity to go beyond the letter of the law to live by the root of the law: Love. God calls Joseph to do what God is doing. God too is righteous. God too could have looked at the human race in our neediness and wantonness, and God could have walked away. God could have killed Adam and Eve in the Garden. God could have killed Noah in the flood. God could have let the children of Israel remain in slavery in Egypt, or killed them with starvation and thirst when they complained about their freedom. God could have put away Israel because of David’s sin, could have destroyed the people under the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, the Romans. But God didn’t. God loved anyway. God left the garden too. God gave the rainbow to Noah as a promise that God would overlook human sin. God wandered the desert in a tent and received no sacrifices when the Israelites ate only manna. God tied God’s honor and glory to the honor and glory of David. And when Solomon’s temple was destroyed, God went into exile, too. And now, God has come to Joseph in a dream. God has come to Joseph in the life and faithfulness of Mary. God is coming in the flesh and bones of Jesus. And beloved, God is still coming in flesh and bone. Matthew’s gospel is represented by a human face to remind us to look for God hiding behind human faces. God is with us in those we would prefer to put away quietly. God is with us in solidarity with the human condition, choosing our lot as God’s own, making our needs God’s needs. Making our suffering God’s suffering. Making our joy God’s joy. This is love; choosing to live in solidarity with another until their problems are our problems, their joys are our joys, their lives are our lives. Joseph shows us what it is to love, what it is to live in solidarity, by hearing and trusting the call of God to take Mary as his wife and Jesus as his own son. We too have the opportunity to live in this solidarity, seeing God in the human faces we encounter in our work, in our world, in our homes, and even in the mirror. God is coming in the flesh. O come to us, abide with us, our God, Emmanuel!! Amen.

I grew up singing in church. I didn’t grow up a Lutheran, and so, the hymnody I learned was not the baroque melodies and ancient chants of the early and medieval church, but the old timey, shaped note, and bluegrass tunes of early 20 th century Appalachia. When I was growing up, the church choir sounded more like the Grand Ol’ Opry than a grand old opera. There was no pipe organ, only a piano, and a reluctant pianist, who was more talented than confident. There were a few different choir directors in my time there. This position was usually filled like the pianist’s position; whoever could say “no” least convincingly ended up with the task. It was pick-up choir. We didn’t rehearse, and everyone who wanted to was invited to join us from the congregation. It was often a 50/50 or 60/40 split between choir and congregation. It was in this church singing that I was introduced to the Spirituals. Songs like “Were You There?” “Sweet Little Jesus Boy,” and “Sweet, Sweet Spirit.” These songs moved me in ways that the other old-timey music we sang never did. Singing in church turned into singing in school, where I learned more Spirituals, like “Elijah Rock,” “Soon I Will Be Done” and a cadre of Spirituals arranged and composed by Jester Hairston. In his autobiography, Fredrick Douglass writes about his experience as a slave in Maryland before his escape. Douglass writes about the songs the slaves sang. He writes: “[These songs] told the tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. … I have been utterly astonished, since I came to the North, to find persons who could speak of the singing among slaves as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.” This as all made me wonder, What should we make of Mary’s singing? How should we hear Mary’s words? What tune was her heart singing that day? Would her happy words be set in a minor key, or in ecstatic exaltation to make the Hallelujah Chorus sound like a radio jingle? Our gospel reading today is a song that Luke’s Gospel tells us arises from the heart of a young girl, visited by an angel, pregnant before her arranged marriage, sent away to live in secret with her distant cousins, in a land occupied by a foreign power. When she arrives at her hiding place, her secret is known, even by the baby in her cousin’s womb. Mark Lowery’s “Mary Did You Know?” is a sweet song, but the better question is, Mary, did you cry? Did you stress eat? Did you doubt? Were you afraid? Were you embarrassed? Did you hold the hand and wipe the brow of Elizabeth as she gave birth to John? Did this terrify you? How did you bear the weight of being “blessed” for “all generations?” Were your hands raised to the sky as your soul magnified the Lord, or did your tears wash the dust from your face? As Douglass reminds us, spontaneous singing ought not deceive us into believing that the joy of Mary’s song was somehow proof that Mary’s ankles didn’t swell, that her back didn’t hurt, that she didn’t have morning sickness or weird cravings, or that this child now “with child” wasn’t overwhelmed by the enormous weight of all that she knew. Mary sang to remember; to remember the promises of God, to remember the promises of the angel, to remember the faithfulness of God, the goodness of God, the mercy and justice of God. Mary sang to remind us, of God’s promises, and faithfulness, and goodness, and mercy, and justice. Mary sang to remind God. Mary sang to “breathe the prayer and complaint of bitter souls boiling over in anguish…. a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” A prayer to God to scatter the proud in the thoughts of their hearts, and to scatter proud thoughts in her own heart. A prayer to God to bring down the mighty and raise up the lowly, and to make sure she was one of the lowly ones. A prayer to God to fill the hungry with good things and send the rich away empty, and to trust that what filled her now was indeed a good thing. Mary sang for joy, a joy born of anguish transformed, sorrow transcended, suffering transmuted. Mary’s song did not spring from her joy. Mary’s joy sprang from her song. Beloved, Mary’s song is a form of prayer we have long neglected. Mary’s song arose from her willingness to embrace the reality that was. Mary’s song, and the songs of slaves were not weak resignation to the suffering of the moment as God’s divine, inscrutable plan, but blessed assurance in the nearness of a God who suffered with them, the steadfastness of a God who would deliver them, the justice of a God who would vindicate them, and the power of a God who transforms pain into comfort, sorrow into solace, suffering into relief, and death into resurrection. Mary’s pondering of the angel’s greeting and treasuring the truth in her heart reconciled her to the harsh reality of the world as it is, and grew in her the hope of the world to come. When we allow these songs to rise up in us, to well up in our hearts, and minds, and mouths we too have joined Mary’s song, the song of hope for slaves, the oppressed, the hungry, the lowly. We have become the mother of God, bearing life and hope and salvation into the world by our song, by our prayer, by our joy. Amen.

Of all the Christmas cards I’ve ever seen, I have never seen one featuring a wild-eyed desert mystic wearing animal skins, honey in his beard and a bug leg stuck in his teeth, yelling, “You brood of vipers!!” It’s the second Sunday of Advent. If you’ve been around for Advent before, you may have braced yourself for John the Baptist - an apocalyptic street preacher whose “good news” sound more like a dire warning. Maybe he missed the “Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem” part of Isaiah’s prophetic poetry. The curmudgeonly prophet raises his voice and lets us have it: "You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruits worthy of repentance." If you’re looking for a soft, comfortable entry into the season before Christmas, John is not your guy. There’s nothing “lowly and mild” about child of promise. The Gospel of Matthew makes a point of telling us that John both appears and cries out in the wilderness, in a landscape that is desolate and barren. Why the wilderness? Why the lonely desert for our Advent reflections? Well, if you have any experience with real estate, you know the mantra: “Location location location.” Location is key. The place where we stand, the terrain we occupy, the space from which we speak — these things matter. While it’s unlikely you’ve ever seen John the Baptist featured in an Advent calendar or on a Christmas greeting card, all four Gospels place him front and center in Jesus’s origin story. John’s austerity is the only gateway we have to the swaddling clothes, angel's wings, and fleecy lambs we hold dear each December. And as baffling as it may seem, the holy drama of the season depends on the disheveled baptizer’s opening act. But why the wilderness? Wouldn’t John be more successful yelling in the center of town - at the gate of the emperor? Well, let’s look at the scene Matthew is setting. John comes from the wilderness to the Jordan. The crowds, including the Pharisees and Sadducees, come from Roman occupied Judea, from civilization. On one side of the river is the wilderness, a place of vulnerability, risk, and powerlessness. In the wilderness, there is no safety net, no Plan B, no rainy-day savings account, no quick fix, and no 24hr grocery store, which means if all you can find to eat are locusts and wild honey, you’re having sweet grasshoppers for dinner. In the wilderness, life is raw and unsettled, and illusions of self-sufficiency shatter very quickly. On the other side of the river is Judea, Jerusalem, and imperial oppression. When these city folk come to the river, they find themselves on the outskirts of the peace through strength offered by Rome. It is a place where the soft neediness of our common humanity is exposed. In the wilderness, people have no choice but to wait and watch as if their lives depend on God showing up, because quite frankly, they do. It is into this environment so far removed from safety, an environment so formless, so void that the Word of God speaks, and what we learn about ourselves in this environment will be as hard to swallow as honeyed insects. John cries from the wilderness, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near!” Crowds stream out of the cities and towns, out of the jurisdictions of Herod and Caesar, out of the promised land to its threshold. This river, the wilderness on one side and the land of milk and honey on the other, is the way to freedom. Slaves and wanderers waded in and the redeemed people of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob walked out. John now calls this redeemed people back, back to the wilderness, back to the doorway, back to the waters of salvation. Repentance is the path of return, to meet the wander in the waters and to walk out redeemed. These words, “sin” and “repentance” are quite loaded, even avoided in modern Christian circles. If you, like me, grew up in a fundamentalist circle, the word “sin” and its association with shame, guilt, and condemnation likely bring a good amount of discomfort. Many of us also distrust the word of scripture because we've seen how easily it can be manipulated to justify one moralistic agenda over another. Yet Advent begins with an honest, wilderness-style reckoning with sin and we can’t get to the manger unless we go through John the Baptist, and John is all about repentance. Does all this talk of wilderness and repentance mean there is no room for comfort at all? If we’re able to get past being triggered by John’s words to follow him out into the wilderness, perhaps what we’ll find is comfort - comfort in the fact that something more profound is at stake in our souls than personal moral failure and private reconciliation. Perhaps what ails us is something deeper, grimmer, and far more consequential. Growing up, I was taught that sin was "breaking God's laws," "missing the mark," "committing immoral acts," or “anything that separated me from God.” These definitions aren't wrong. They’re just incomplete. They don’t go far enough. They don't name the fullness of all we struggle with. Sin, at its heart, is a broken relationship to reality itself. It's anything that interferes with the opening up of our whole hearts to God, to others, to creation, to our very selves. Sin is estrangement, disconnection, disharmony. It's the sludge that slows us down, that says, "Quit. Stop trying. Give up. Change is impossible. I’m not responsible for my actions. You’re not my problem." In other words, sin is apathy, care-less-ness, the frightened resistance to an engaged life. It is the opposite of creativity, the opposite of abundance, the opposite of flourishing. Sin is a walking death. And it is easier to spot, name, and confess a walking death in the wilderness than anywhere else. We have to be confronted before we can be comforted. This is why John underscores his message of repentance with a harrowing description of the coming Messiah: "He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor and gather the wheat into the granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire." If you weren’t squirming before, I bet you are now. How in the world is this good news, this portrait of a Jesus with pitchfork and fire who judges, sorts, and burns? In Malachi 3, the Lord says, “I will draw near to judge you.” Often, we equate judgment with condemnation. But what if God was saying “I will draw near so I can see you better.” What if John is saying that the coming Messiah really sees us? That he knows us at our very core? That the winnowing fork is an instrument of deep love, patiently wielded by One who wants to separate from us all the dried-up husk that we once used to protect the precious seed within? Perhaps then, it's in offering God every piece of our lives that we give God permission to "clear" us — to separate all that's no longer useful from all that is good, beautiful, and worthy. John calls us to return, to come back to the water, to the threshold, to re-enter civilization, no longer a slave or a wanderer, but as citizens, neighbors, in a promised society. God calls us to the water to make peace by making justice, with God, within ourselves, among each other. When this happens, the wilderness and our lives, become a place where we can see the landscape as a whole and participate in God’s great work of leveling inequality and oppression. “Prepare the way of the Lord,” John cries, quoting the prophet Isaiah. “Make his paths straight.” We prepare for the coming of Jesus by becoming accountable individuals within a just society. We are called by our baptism to accountability and responsibility for the way of the world. Accountability and responsibility make justice. Justice makes peace. Peace prepares the way to a better world. Amen.

When I was in middle school, my grammar teacher was terrifying. He was the sort of teacher who commanded silence by his very presence. I do not ever remember there being a disruption in his class. He taught from a desk in the front of the class room, which he had modified to contain an overhead projector, which he used instead of the white board. He was then able to sit facing the classroom, never turning his back to us. Day after day, we were all subjected to lesson after lesson on grammar; syntax, diagramming, punctuation; I learned all of the helping verbs by heart to the tune of “When the Saints Go Marching In” so I would never use the past tense of a verb when I should have used the past participle. But then I became one of those people. One of those people who correct people’s grammar. More precisely, I became a 12-year-old who corrected the grammar of adults. I couldn’t believe how many of the adults in my life didn’t know or didn’t care that they were using the wrong verb tenses all the time. I also couldn’t believe how many of the adults in my life didn’t appreciate being corrected. Didn’t they want to speak English correctly? I mean, language needs to be precise. It is one thing to say, “I seen a deer this morning.” But the stakes are a bit higher if you forget the comma in the sentence, “Let’s eat, Grandma.” Because, “Let’s eat Grandma” means something a bit more sinister. With mastery, language can give us control. Grammar and dialect can expose our education and socio-economic status. Mastery of the rules about what is vulgar or profane and what is polite or elegant becomes mastery over those whose language makes them vulgar or profane. This mastery can remove ambiguity, making it easier to convey instructions, commands, ideas, emotions, even over great distances. Even over centuries. Mastery of the languages of the Bible— Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, Latin— have given interpreters a great sense of confidence that they are conveying the ideas of the original languages to us in their translations. We can hear the metaphors of Jeremiah as he describes these bad shepherds and how God will gather the scattered sheep from all the places they’d been driven. We can hear the esoteric cosmology of the author of Colossians as he tells us that Christ is firstborn of Creation and of the dead. And we can imagine the historical scene described to us in the Gospel of Luke, vivid in the horror of what it describes, and yet pallid in its sanitized familiarity. Making meaning of these readings in hard. We want to be able to skim the surface of these texts and understand their meaning like mining for diamonds with a boom and dustpan. But where we want mastery the texts often give us only mystery. Here in this passage from Luke, Jesus speaks to those crucified with him. Jesus says to the one who asks to be remembered, “Today you will be with me in paradise.” In an attempt at mastery, the translators have added a comma. The original Greek doesn’t have commas. The original Greek doesn’t even have punctuation, not even spaces between the words. The original Greek leaves us with an uncomfortable ambiguity. Does Jesus say, “Truly I tell you, Today you will be with me in paradise?” Or does Jesus say, “Truly I tell you today, you will be with me in paradise?” Where we want mastery, to know exactly what Jesus meant, the text gives us only mystery. My inner 12yo loves knowing the right answer, especially when others do not, especially when it allows me to think of myself as better, or brighter, or in control. But the reign of Christ is not about mastery. In the reign of Christ, I am not in control. In the reign of Christ, I don’t have to be better or brighter. In the reign of Christ, I don’t have to know where all the commas go. In the reign of Christ, God is calling us to ministry instead of mastery. I don’t have to have mastery over the cosmos, over theology, over the syntax of sin and salvation, or even over my own life. In the reign of Christ, we can embrace the sacred mystery, the great unknowing. We can take a deep sigh of relief at not having to have all the answers. Where we want mastery, Christ gives us mystery and the call to ministry. God is not some terrifying grammarian teaching us the rules and grading our homework, modifying our native dialects and polishing our heart tongues until the empire can see its own reflection. God is often nonverbal, humming tunes in vagal tones we only understand by being held close. God’s love is not bound to syntax and structure, but is free and syncopated, speaking in image and analogy, silence and epiphany, instead of imperative and exclamation. In the reign of Christ, there are no kings, no bad shepherds who divide the flock to keep control, no thrones or rulers or dominions or powers. The reign of Christ has come, Beloved, without punctuation, without even a space between this age and the one to come. Amen.

Well, what an uplifting set of readings! In the first reading we get the coming of a day burning like an oven that will consume all the arrogant and evildoers, leaving not a trace behind. On to the second letter to the Thessalonians, where we are admonished against idleness, warning that those unwilling to work should not eat. And finally, Jesus gives us a cheery picture of the future, filled with false teachers, wars and insurrections, earthquakes, famines, plagues, portents in the heavens, arrest, imprisonment, beatings, martyrdom, and the destruction of the center of Jewish life and worship. If you came to church today to feel better, how am I doing so far? Probably about as well as your favorite news source. Jesus could have pulled this list from the headlines on CNN.com. There is ongoing war in Ukraine, as well as in Sudan. There is a tenuous ceasefire in Gaza, which Israel has already violated, and the whole of the Gaza strip has been leveled, tens of thousands killed, humanitarian aid blocked, and a manmade famine killing thousands more. Our own national politics has caused quite a bit of hunger here at home, with SNAP benefits in jeopardy and food banks inundated with furloughed or unpaid federal workers and those without their SNAP disbursements. Rising inflation has sent food prices and rents soaring. The looming specter of AI and the voracious data centers needed to sustain it has sent utility prices to dizzying heights. The global climate crisis continues to worsen, threatening widespread global chaos. And while we aren’t facing arrest or imprisonment in Jesus’ name and our house of worship is still standing, it feels like everywhere we turn there are stories and studies of the church in decline, dwindling worship attendance, and folks turning their backs on the faith. What if Jesus wasn’t foretelling the end of things, but describing the reality that things end? What if Jesus was just describing the way things are, have always been, always will be? Jesus tells the disciples that the temple they admired would be destroyed. In fact, this is already the second temple, because the first one was destroyed. The second one was desecrated by the Greek occupiers and had to be reconsecrated. And by the time Luke’s audience was hearing this Gospel, the second temple had been destroyed too. Tragedy is inevitable. There will be war and famine, fires and floods. There will be plagues and hurricanes; we will act in ways that bring destruction. Tectonic plates will shift, mountains will rise and fall. And none of this will be the end of all things. Instead of growing weary, instead of cowering in fear, instead of paths that lead to destruction, Jesus invites us on a path that leads through destruction, through calamity, through death. This path leads to a promised future in which the sun of righteousness will rise on the just, with healing in its wings. This path leads to a promised future in which God’s judgment looks like steadfast love and faithfulness. Jesus is calling us to move forward along this path, with our history in one hand and our hope in the other. Jesus is calling us to move forward along this path, to not grow weary in doing what is right, but to set our eyes on the cross of Christ knowing that the cross is the nature of the path. It will pierce us. It will bruise us. It will even kill us. But it will not destroy us. We, with Christ, will rise with scars in our hands and feet, with splinters in our backs, with sweat and blood dried to our brow. The cross will not have the final say. Love will have the final say. Because our hope is in a God who is Love. Because our history is the triumph of love over loss. The path will be long, and difficult, and wounding. The path will be fraught with grief, with injustice, with war and famine and plague, with disasters of our own making, and seismic shifts to level the mountains and fill in the valleys. But God in Christ is on this path with us. God will not abandon us, even in death. Because the path is not the destination. The path leads us through the valley of the shadow of death to the green pastures where our soul may dwell in the house of the Lord forever. So in the meantime, do not grow weary in doing what is right. Work for the good of others, allow the path to change you and the world around you. Discipleship ain’t for punks. God is using the path to transform us to redeem us, to evolve us, to save us. And in the end of all things, when we have come to the end of the path, when we can see the first light of the dawn of righteousness, when judgement comes with steadfast love and faithfulness— in the end of all things, Love will be all there is. Amen.

Sheesh. After reading the passages this week I came away with one central question; Why does the Revised Common Lectionary hate preachers? At this point in the lectionary, we are turning our attention toward the reign of Christ and the beginning of a new liturgical year in Advent. We see some of this in the talk of resurrection in the Gospel, in the coming of the Day of the Lord in II Thessalonians, and Job’s hope that he will see his redeemer in the flesh. But none of these passages are about what appears on the surface. Job seems to be about the resurrection, but that would be impossible. Job is the oldest text in the Bible, written in a time before the Hebrew people began to articulate a theology of resurrection. Eventually, as generations died in captivity to Babylon and Assyria, and Persia, and Greece, Hebrew theology had to contend with the fact that if justice didn’t come before death, then either God is not Just, or there must be existence beyond this life in which God’s people will experience justice. At the time of the writing of Job, one lived on in the legacy of one’s heirs. And Job has lost all of his. Job’s defiant hope that after his skin is destroyed, in his flesh he will see God is his hope that he will experience God’s vindication before death. The story of Job continues, and that is exactly what Job experiences. In II Thessalonians, the church in that city seems to have heard a rumor that they have missed the second coming. The writer advises their readers they should not pay any attention to hearsay or letters that pretend to be from Paul and his companions but are not from Paul and his companions. Here’s the kicker: II Thessalonians is almost certainly not from Paul and his companions. Where does that leave a preacher? Then there is the Gospel reading, where the Sadducees give Jesus a parable about marriage to try to trap him. The Sadducees hold what we might call an originalist interpretation of the Torah, the first 5 books of the Hebrew Scripture. This is Genesis, Exodus, and the books of the Law, wherein there is no mention of resurrection. Like Job, the Sadducees believe that there is nothing after death, so they use the Law to try to trap Jesus, trying to prove that Moses gave this rule about Levarite marriage— marrying the widow to her brother-in-law to try to produce offspring for the deceased— as proof that there is no resurrection. Jesus response to this legal inference is to say something like “Marriage-schmarriage. in the age to follow the resurrection there will be no such thing as marriage.” What is going on here? Job, the Thessalonians, and the Sadducees are all waiting on the coming of Justice, the fulfillment of God’s promise. Job has lost everything and is waiting for God’s vindication. The Thessalonians want to make sure the day of the Lord has not already passed. The Sadducees’ rigid adherence to the plain meaning of the Torah has made them incredulous toward the idea of a resurrection. While it still feels like the selection of this week’s readings followed one-too many drinks and someone saying, “Come on guys, we can knock out one more week before we call it a night!” I still see some signs of hope, maybe even some good news. Like Job, we have all experienced loss, change, grief and the need to hope that all of it hasn’t been for nothing. Like these Thessalonians, we are inundated with late-night televangelists, influencers peddling rapture survival kits, predicted dates, and Kirk Cameron promising us that the Day of the Lord is just around the corner, and we could miss it if we aren’t careful. Who knows what to believe about the second coming anymore? And when we have big, cosmic questions about how to cope and what to believe, like the Sadducees, we want to turn to the Scriptures, we expect that they will speak to us plainly and that they will never change. But looking closer, we see that, when pushed to his limits, Job’s hope is beyond the scope of his theology. The mystery writer of II Thessalonians honors the legacy of Paul with a sort of fanfiction to assure the church that they haven’t missed the second coming. And Jesus takes the Torah seriously even as he broadens the interpretative lens to see in the resurrection an end to exploitation. You see, it was the men who took a woman to marry, and it was the women who were taken. It is this exploitative, entrapping, misogynist taking and being taken that Jesus promises will end in the age to come. Your marriage now and ancient near-eastern marriages then are two totally different things. And yet, then as now, marriage will not be defined by the rigid legalism of a tiny group of self-styled traditionalists who’s love for some old document prevents them from loving their neighbors. If these scriptures and their promises really come to us from God, then this God must be bigger than, greater than, and sovereign over these scriptures and these promises. God is not bound to the scriptures or the traditions we have created to hold them sacred, or the theological frameworks we have devised to make them make sense. And when these ways of reading, keeping, thinking through, and believing no longer work, God is still faithful and calls us to reinterpret the promises for the present age. DISCLAIMER: The following statement is intended for spiritually mature audiences only! Hearer discretion is advised. The Bible is not the Word of God. Jesus is the Word of God. The Bible contains and our worship proclaims the Word of God, that is Jesus Christ. We are not called to be defenders of the Scriptures, of tradition, of theological heritage; much less are we called to be defenders of God. We are called to be followers of Jesus, to love God and each other. If and when the circumstances of this life force us to choose between our neighbors and defending the scriptures, our traditions, or our theological heritage, we are to choose our neighbor EVERY. SINGLE. TIME. Ok, so maybe the Revised Common Lectionary isn’t so bad after all. Maybe this preacher just wished that the meaning was a little plainer. But having dug a little deeper, having wrestled a little more, I am glad we hung in to find this deeper meaning. Jesus Christ is the Word of God, contained in Scripture and proclaimed in our worship. Now may our Lord Jesus Christ himself and God our Father, who loved us and through grace gave us eternal comfort and good hope, comfort your hearts and strengthen them in every good work and word. Amen.

History is complicated. When I first entered college 25 years ago, I was a history major. I took many fascinating classes, and learned a lot of information about a number of things. The most eye-opening course however, was Historiography. Historiography is the study of how to write history. The study of History itself can take two different tracks; one is the exploration, recovery, and recording of historical events in chronological order, a bare statement of facts and figures, a bit like retroactive journalism. This is the stuff of archeology, anthropology, paleontology, even theoretical physics as it explores the universe to better understand how this universe came to be. It is largely a scientific pursuit. It relies on empiricism, verifiability, evidence, hypotheses and testing hypotheses, until a reliable record of events can be reviewed by one’s academic peers and broadly accepted as the facts about a given subject. Every attempt is made at neutrality, writing as unbiased a record as possible in hopes of leaving future generations as clear a picture as possible of events as they happened. The other track is interpretation of the facts. These historians take the facts and make meaning from the bare record, writing the story of a time, a place, a person or a people, to help us understand not just what happened and how, but why it happened, and what it means for us now, how we might avoid the same mistakes or repeat the same triumphs. These narratives become part of who we are, how we understand ourselves and our place in the world, how we justify or make amends for our actions in the past, how we explain ourselves to others and to ourselves. And this is where history gets complicated. The first type of history can change. As new evidence comes to light, archeological discoveries are made, and new technologies produce more capacity to extract and examine more information, the historical record can change, replacing misunderstanding and misinformation with better understanding and better information. Most Americans know the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, when as a child, George uses his new axe to chop down the prized tree. When confronted by his parents, George fesses up, famously saying, axe in one hand, the other over his heart, “I cannot tell a lie.” Thus, Washington looms large in our hearts as the epitome of the ever elusive “honest politician.” So, it is of little note and almost no consequence that there is zero evidence that this event ever transpired, meaning that though the story is factually false, it still contains some sort of truth we felt we needed. We needed a truth that bare facts could not supply. And we don’t tend to like it when facts get in the way of the meaning we have made. Today, we celebrate All Saints’ Day, a day set aside to remember our history. A day to honor those faithful believers who have gone before us to show us the way of grace and truth. We remember those sainted dead, those holy foremothers and fathers, who lived this life of faith before us and whose stories tell us who we are. We recall grandparents and parents aunts and uncles, siblings, friends, pastors and Sunday School teachers, camp counselors and Bible study leaders, campus ministers and youth group leaders, spouses, colleagues, and acquaintances who loved us into the Kingdom of God and have now shuffled loose this mortal coil, existing just beyond our grasp. And as we recall these fond memories it’s often not the facts that we recall, but the stories, the tales of meaning that have endeared these saints to our memory and knit their lives into our very identity, and our very identities into the life of God. But when we recall the stories without an ear to the facts we often diminish the truth and weaken the story. We have not come to this point in the history of the world or the history of the church “standing on the shoulders of giants” as we like to imagine. Rather, we have come here upon a hill of skulls a mountain of death and sin, and pain, upon the Cross of Christ. There are no saints who were not first sinners. There are no saints who were not first redeemed. There are no saints who have not come through the great ordeal and washed their robes in the blood of the lamb. When we tell the stories without the facts we deceive ourselves into thinking that we might be able to live this life without pain. That we might escape misfortune, suffering, death. That those saints were somehow spiritual superheroes, or that life was less complicated back then. But Jesus tells us otherwise. Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor.” Jesus does not say “Cursed are the poor.” Jesus does not say, “If you really believe in me, you won’t be poor.” Jesus doesn’t say, “It is God’s will that you should be poor.” No, Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor.” Blessed are the hungry; Blessed are those who weep; Blessed are the rejected.” AND “Woe to the rich, woe to those who are satisfied, woe to those laughing now, woe to those with good reputations.” Jesus says that life in this world will bring poverty and wealth, hunger and satisfaction, weeping and laughing, with rejection and good repute. Jesus is laying out the facts, giving us the evidence, giving us an accurate picture of the way of the world. But Jesus, like a good historian, is also giving us a story, making meaning of the facts. Jesus tells us that the bare facts will not define us, nor will the grand sweep of history consume us. Neither poverty nor wealth, hunger nor fullness, weeping nor laughing will last forever. This life is filled with tragedy and celebration, pain and pleasure, loss and leisure, suffering and satisfaction, death and resurrection. And God is making meaning of it all. God is telling a story, a truth that takes the facts seriously and is yet bigger than the sum of its parts, a truth that makes meaning of all the suffering and sorrow, a truth that makes saints out of sinners, a truth that brings life out of death. We are living in a historic moment. Today is day 33 of a government shutdown, leaving federal workers unpaid and relying on food banks to eat. These already strained food banks are now the primary source of food for some 42 million neighbors who rely on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP— formerly food stamps— to eat and feed their families. Jesus’ advice to his followers in light of the facts of life, the blessings and woes, is that we should treat others the way we want to be treated. As we look back at the saints who brought us here, we must also look in the mirror, at the saints God is calling us to be. The hungry are blessed because Jesus calls us to be a blessing. The late Pope Francis said, “First you pray for the hungry, then you feed them, because that’s how prayer works.” Beloved, we are the saints. We have come through blessing and woe, hunger and fullness, weeping and laughing, to possess this kingdom of God in this very life. This is what made those who went before us saints, and this is what will make those who come after us saints, that by the Love of God, in spite of all the facts, God is making meaning of all life’s blessings and woes, turning us toward each other in Love, in goodness and prayer, in nonviolence and generosity. God is making meaning of the facts of this life by making saints of each of us, so that, with the eyes of our heart enlightened, we may perceive what is the hope to which we have been called, the riches of God’s glorious inheritance among the saints, and the immeasurable greatness of God’s power in Christ for us who trust in the truth according to the working of his great power. So, give to the poor, feed the hungry, comfort the weeping, and let your reputation be that of a redeemed sinner in this life. This is a life with meaning. Amen.