Sermons by Pastor Ashton Roberts

For those who find it helpful to read along while Pastor Ashton preaches.

Sermons by Pastor Ashton Roberts

Have you ever been tempted? Really tempted? Not “should I have a second dessert?” tempted, but really, really tempted? Like, more cheat-on-your-taxes tempted and less cheat-on-your-diet tempted? Please don’t raise your hands, this is being broadcast on the internet. IRS, if you’re watching, this is purely a hypothetical, rhetorical exercise and not an accusation, assumption, revelation, or confession. Temptation works, not because we don’t know right from wrong, not because we are so evil as to consciously and willfully choose evil, but because we are bound to choose the good and what seems good to us is, in these moments, the unethical, immoral, or temporally more pleasurable option. In fact, we will always choose what seems to us to be the better option. Even if we are choosing the evil option, we are, in that moment, in that choice, convinced that the evil option is the better option. We cannot choose evil without believing it to be good. Our first reading and our gospel reading are both about temptation. Adam and Eve are tempted to be like God, framed in this story as “knowing good and evil.” Jesus is tempted to meet his own needs by means of power rather than trust and obedience. And really, these are the same problem. Adam and Eve believed that if they could know good from evil they could choose the good and be like God. Jesus was tempted to be self-sufficient in the wilderness, making food, making God prove Godself, and taking the shortcut to the Reign of God— that is, Jesus was tempted to be like God as humanity had conceived of God rather than like God as God is. And this is our temptation too, that we could be like God, if we knew right from wrong and had the power to choose. We could be independent, sovereign, without any need or responsibility. So, we set out to keep the Law, to judge right from wrong, and to set about keeping God’s rules. And then, choosing good and abstaining from evil, we will be good and free, just like God. And when we are good and free like God, God will love us, want to be with us, will bless us, protect us. But the dark side of this belief is that when we have done all this good and have enjoyed all this freedom and bad things still happen, loss still comes, death still haunts us, we conclude that the whole story was a lie and we have been duped. Or, we spiral in to shame and despair as we begin to realize that all these rules cannot be kept perfectly and we aren’t measuring up. We begin to see all the good choices we did make like a loincloth of fig leaves, barely obscuring all we’d rather hide. God doesn’t give us the Law so we will know good from evil. God gives us the Law to show us who God is and how God acts, and therefore, who we are and how we ought to act. In this creation story from Genesis, Adam and Eve are banished from the Garden. And God goes with them. God does not stay in the garden. Adam and Eve and God leave the garden. Adam and Eve and God enter the wilderness together. Adam and Eve succumbed to the temptation to be “like God” because they failed to trust that they were already created in the “image and likeness” of God. Jesus does not succumb to the temptation to be like God because he trusts that the Law reveals who God is and how God acts. Jesus reveals that God is with us in the wilderness. We are already loved, not because of what we do or abstain from doing, but because of who God is and how God acts. We have the law to show us God’s mercy and grace and to teach us to act with mercy and grace. We are not the worst things we have done. But neither are we the sum total of all the good things we have done. We are what God says we are, and that is very good. We are chosen. We are loved. We are good. We are guided by the Law of love. And when we have erred, when we have sinned, when we have fallen short, when we have not lived up to who God says we are or acted as we ought to have acted, We are chosen, we are loved, we are good, and we are guided by the law of love because that is who God is and how God acts. And that seems pretty good to me. Amen.

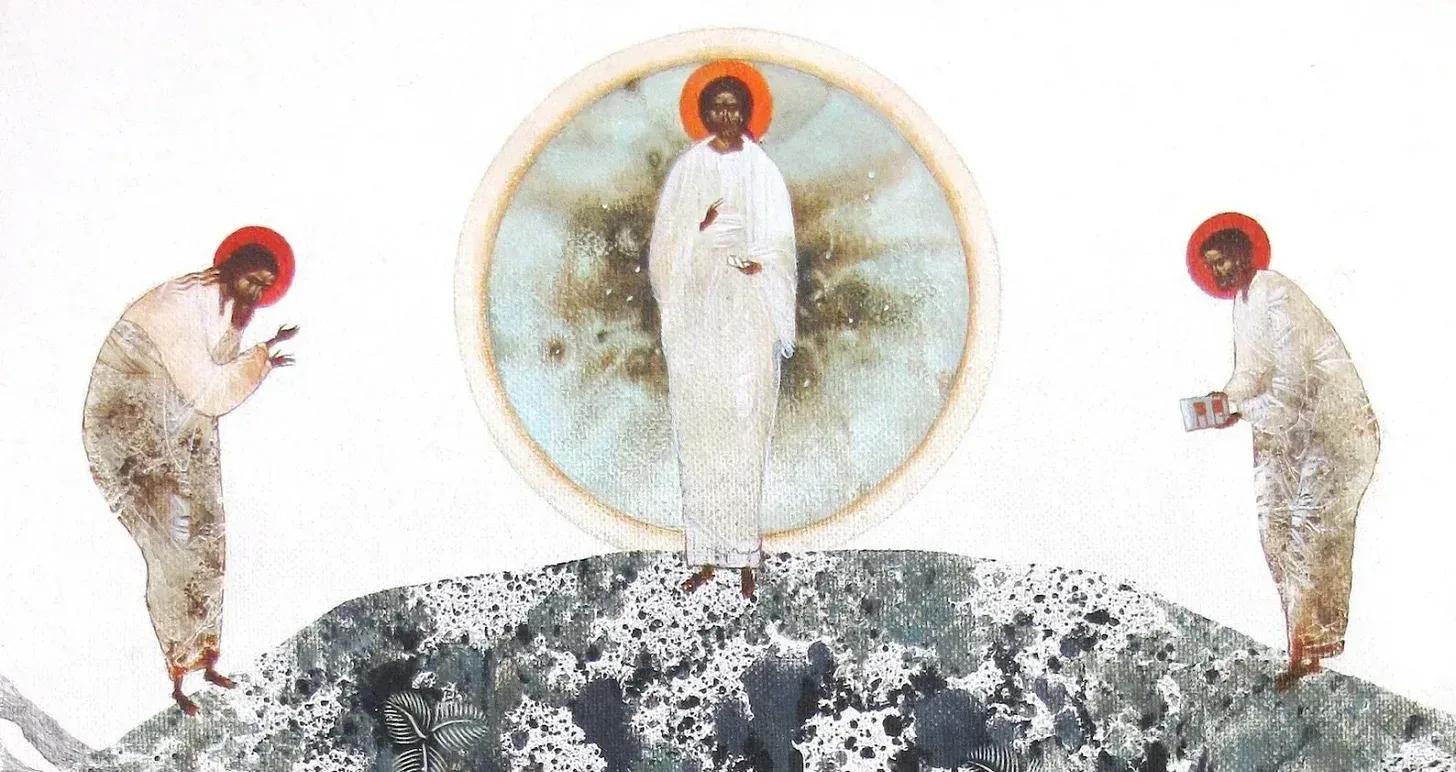

We have come to the end of the season after Epiphany. This liturgical season begins, as the name might imply, with the Feast of the Epiphany. And as the term “epiphany” might suggest, this season is about revelation, the experience of God With Us, first in the person of Jesus, and then in our very lives as we hear the call to follow Jesus as disciples. We begin at the river Jordan, where Jesus is baptized by John, and a voice from heaven declares Jesus to be God’s beloved child, a declaration spoken over all those who are baptized into Christ. We heard Jesus call Peter, James, and John to give up fishing for fish and join Jesus in fishing for people, and we heard in this call that Jesus doesn’t call disciples away from their lives but to their lives, to engage with their lives, families, and work as disciples. Then we heard Jesus begin to teach his followers using the phrase, “you have heard it said,… but I say…” to show his disciples that they are living in a world upside down, and the reign of God has come to turn the world right-side up. In our worship here we have used a more casual form of the liturgy to help us see that what we do in here has bearing on what we do when we leave here. In today’s Gospel Jesus takes three of the disciples, Peter, James, and John, up a high mountain to pray. There he is transfigured before them, flanked by Moses and Elijah, and affirmed by a voice from heaven repeating the words from Jesus’ baptism, “This is my beloved son,” and adding “listen to him.” These three disciples are at first honored by this experience, and then quickly humbled by the voice from heaven. My hope is that our worship in this season has made you feel a similar sense of familiarity and awe, of intimacy and wonder before the presence of God in the Sacraments and in each other. But I also wonder about those other 9 disciples, still at the foot of the mountain, waiting and wondering what is taking so long. I wonder if they felt left out, like they had missed something. Did they wonder if they had done something wrong? Did they wonder if their faith wasn’t strong enough, deep enough? Did they admire the other three, or resent them? Did they resent Jesus for leaving them behind? I imagine it’s possible that you have come through this season after Epiphany feeling like you’ve been left at the bottom of the hill. Maybe you feel like all this talk of God With Us has not led to an epiphany for you, that finding God in your daily life feels more like the sort of thing that happens to other people. Maybe it is easier to believe that Jesus is God in the flesh than it is believe that God has any interest in your flesh. We tend use light as the primary metaphor for this season after Epiphany. We talk of Jesus as the light of the world, and we talk of light banishing darkness, as though light were a metaphor for the goodness of God and darkness were the metaphor for evil. But I think this is a misinterpretation of this metaphor. We need the dark. Without the dark, we could not sleep deeply enough to rest and recover from our day’s labor, and prolonged periods of sleep produce all manner of unhealth, including cardiac arrest and psychosis. Plants and animals need periods of dormancy to thrive and grow. The darkness is not our enemy. But the darkness can keep us from seeing our path. We also need the light. But when we walk into a dark room and turn on a lamp, we don’t stare at the bulb, praise the bulb, worship the bulb. When we walk into the dark room and turn on a lamp we can see the room for what it is. We can see our path through the room without stubbing our toes, tripping over furniture, walking into walls. We can find objects obscured by the dark, see the patterns on fabric and paper, the colors of dyes and paints. We can see to read, knit, sew, craft, cook, eat, work. The light of the lamp, the light of the room, becomes the light by which we see. This is what we mean when we call Jesus the light of the world. Jesus is the light by which we see. Jesus is the light by which we see the path through this life, with all its obstacles and challenges. Jesus is the light by which we see that God is even hidden in the darkness, in the patterns of this world, in all its beauty and tragedy. When Jesus tells Peter, James, and John not to tell the story of his transfiguration until after the resurrection, Jesus is not telling them to keep a secret, nor to hold onto a private revelation that is only for a chosen few. Jesus tells these three not to tell an incomplete story. Jesus knows that the glory and majesty of God is an incomplete story without the terror and tragedy of the cross. The experience of God in the flesh is personal but never private. In our Epistle reading we hear Peter telling the whole story, the complete story, the story that includes both his experience on the mountain and his betrayal at the cross, the glory of transfiguration and the tragedy of crucifixion. Peter had to go through the whole story before he could tell the whole story. The revelation of God in Jesus is the light by which we see that whether we ascend the mountains or find ourselves in the valleys, God is with us. The experience of the presence of God is not a private reserve, doled out to a select few. The promise of the presence of God is the confident announcement of the Gospel. And this confident announcement comes to us in the waters of our baptism, in the bread and wine on this table, in our hands, on our tongues, in our bellies. It comes to sinners made saints. It comes on the mountain and in the valley. It comes to the #blessed and the #stressed. It comes in the light of certainty and the shadows of doubt. In the season of Lent, we will hear that even Jesus wrestled with the temptation to doubt God was with him. We will hear from Nicodemus in the dark of night and the woman at the well in the bright light of day. We will hear from a man born blind and Mary and Martha by the tomb of Lazarus. And we will again ascend the mountain with Jesus and stand at the foot of the cross, before we again see him transfigured in the light of the resurrection. The season after the Epiphany invites us to experience God with us, and Lent invites us to find that even in the darkness we have not been abandoned. So Beloved, Get up and do not be afraid. Jesus is coming down the mountain to meet us. Amen.

I am reminded of a quote from The Office, when after a series of troubling events, Michael Scott says, “I’m not superstitious, but I am a little ‘stitious’.” Are you superstitious? I’d dare say that there are two main options. Either you are too rational, too enlightened and too educated to give in to such nonsense, or you are too beholden to tradition, or etiquette, or historical reenactment to open an umbrella indoors, or to walk under a ladder, to fail to say “bless you” when someone sneezes. Some of my favorite superstitions have to do with pocketknives. It is bad luck to close a knife you didn’t open. Stirring anything, like coffee or soup, with the blade of your pocketknife is bad luck. Cutting hot cornbread with a pocketknife is bad luck. Now with a little thought the origin of some of these can be easily explained. I can see a father handing a child a pocketknife to complete some task and asking that the knife be returned the way it was given in order to prevent the child from cutting themselves. And after seeing pocketknives being used for everything from gutting small game to picking the dirt from your fingernails you don’t have to be a microbiologist to see that sticking the blade in your food is a bad idea. But my favorite superstition has to do with the gifting of a knife. The common wisdom says that by gifting a knife you will soon sever the relationship. So, the work-around became that with the knife you also gift a coin. Then the recipient “pays” you the coin, and this “transaction” preserves the relationship. I love this tradition/superstition because of the love it implies. Not only have you implied your affection with the gift, but with the coin you have implied the hope that your relationship will continue. Now, I have to tell you, Gospel of Matthew is not my favorite. To me, the Good News that Matthew proclaims often feels a lot like getting a knife without the coin. It feels like the good news has come with an asterisk, warning “some assembly required.” The Gospel according to Ikea. Jesus tells us “I have come not to abolish the law but to fulfill [it].” Jesus tells us “Unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” Yikes. It feels like Jesus has given a gift that will soon sever our relationship with God and we’d better come up with enough righteousness to “pay” the giver of this gift before we run out of luck. It’s enough to make Luther roll over in his grave! If the righteousness that God requires of me is something I have to muster up out of my own heart and will then I am surely doomed, and this Gospel is no good news at all. Luckily, that’s not the Gospel at all. The gospel doesn’t start with the law. The gospel starts with God. God who IS Love. When we Lutherans talk about grace, we are talking about the way that Love behaves. We are talking about a God who is love and created the whole world out of that love. We are talking about a God who chose the people of Israel out of perfectly free love and said to them, “I will be your God and you will be my people.” Love precedes the Law. Grace came before the Law. Before God ever said “you shall not eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” God saw the universe God had created and said it was very good. Before God gave circumcision God called Abraham righteous. Before God gave the Ten Commandments, God led Israel out of Egypt. The law is not like the coin given with a knife. The law is not a transaction, not a means by which we ward off bad luck, not like that little hex wrench that comes with Ikea furniture. The Gospel of Matthew is the good news that we are already the people of God, and Jesus is showing us that Grace is how God’s people behave. The law is God’s proclamation “You are mine. Now act like it.” Jesus does not say “if you have faith you will be the salt of the earth. Jesus says “You ARE the salt of the earth. Act like it.” Jesus does not say “If you follow the ten commandments you will be the light of the world.” Jesus says, “You ARE the light of the world. Act like it.” The Good News of the Gospel is that we are God’s people ALREADY. And because we are God’s people we will love those God loves. The righteousness we enact will exceed that of the scribes and Pharisees because our righteousness is Christ’s own righteousness. In the gospel we have not been given a pocketknife and a coin; a token of God’s affection and the means to maintain the relationship. In the Gospel we are given the good news that we are already in the Kingdom of Heaven, that we are already righteous, that we are already God’s people. Now let us act like it. Amen.

As many of you may already know about me I grew up a fundamentalist. I was part of a tiny Appalachian Baptist tradition that believed the King James Version of the Bible was the only divinely inspired version of the Word of God. and therefore was “the only rule of faith and practice,” as the denomination’s charter stated. My faith was forged in the hellfire and brimstone preaching of this tradition and cooled in the soothing melodies of shaped note singing about the sweet by-and-by. My grandparents took me to church starting at age 2, letting me stay at their house every Saturday night, a tradition that only ended when I moved to college. My grandfather had this story about how he had come to the faith, miles underground in a coalmine in southwestern Virginia. One night, working in the deep darkness he cried out to God for salvation and it completely changed his life, and he would spend the rest of his life sharing Psalm 139:8 If I ascend up into heaven, thou art there: if I make my bed in hell, behold, thou art there. as if it had been written about his own life. Eventually, he met and married my grandmother, who came to the faith because of him. My grandfather even had his own radio show, where he would ‘testify’ live, on air each week. Many of the other folks in our church had these dramatic stories of instantaneous conversions where God had delivered them from a life of scandalous sin, and had now written their names in the Lamb’s book of life. When I was 7 years old, I understood that God loved me that Jesus had died for me, and that I wanted to go to heaven. So, when I was told that I needed to accept Jesus as my personal savior, of course, I did. Now, in this tradition, the next thing you do is you begin to learn to share your story, your testimony, as we called it. But I was seven. As you might imagine, my story couldn’t include that Jesus had delivered me from drinking or sleeping around, or gambling, or any of the other things that so many of the other testimonies had included. In fact, my realization that I needed a savior had come as something of a shock because it hadn’t ever occurred to me that I didn’t already have one. My faith had come from the witness of others, from their testimonies. From those whose life experiences had driven them to Jesus, whose conversions had literally saved their lives. But where was God in my own story? What good news did I have to share? In John’s gospel today, we see John’s experience of the Holy Spirit at Jesus’ baptism has led him to point to Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. It is John’s testimony, that Jesus is greater than himself, even offering a baptism greater than his own baptism, that Jesus is the Son of God, that compels his own disciples to leave John and follow Jesus. When Jesus sees John’s disciples following him he asks, “What are you looking for?” John had seen the Holy Spirit descend and confirm that Jesus is the Son of God. Maybe these disciples didn’t know what they were looking for. Maybe they were expecting something like the heavens rending, or voices booming, or a dove descending. We don’t know for sure what they did find, but whatever they found compelled Andrew to go and tell his brother that they had found the Messiah. The season of Epiphany is about recognizing God first in Jesus and then everywhere else. We see from John’s story and from Andrew’s story that God comes to us in the proclamation of the truth about Jesus. God is calling each of us to be preachers and prophets, to first recognize God in our own stories, and then go and tell these stories to others. But we cannot always identify God in our own stories. As I grew in my own faith, I realized that though I couldn’t point to a dramatic rescue or to an instantaneous conversion experience my testimony is that I cannot remember a time when I did not know Jesus. And, it wasn’t until I came into the Lutheran Church and began to hear the stories of folks mostly baptized as babies, who also couldn’t remember a time when they didn’t know Jesus, that I began to hear echoes of my own story. I found that God had been at work in my life the whole time. And I would never have known this without the testimony of others. This good news of God come near in Christ Has been passed from John the Baptist, to the disciples, to the early church, through 20 centuries of believers, into Appalachian coalmines, across AM radio waves, even through fundamentalist preachers. God is revealing Godself not only in the stories of others, but also in your own stories. God is continuing to write the story of the Gospel, in our hearts and lives, through our mouths and hands, calling us to testify to the God come near, first in Jesus, and then everywhere else, that you too may point to God in the flesh and echo John’s proclamation, Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. Amen.

What a busy few weeks it has been. I hope you found some rest to recuperate from the Christmas hustle and bustle. I am always grateful for vacation time, to relax and restore, to come back to work with renewed commitment and the energy to do all the things I have to do. But I imagine I am not alone in discovering that returning to work after a vacation is a bit surreal. It always takes a minute to remember the routines, to remember the passwords, to remember what it is I do on a Monday. My desk looks like my life did in December, cluttered with delayed tasks abandoned in the triage of looming deadlines, a stack of old bulletins waiting to be recycled, hastily written notes that I’m sure made sense when I wrote them, a cup of coffee I didn’t get the chance to finish. And sitting at that desk again I have a hard time trying to locate the renewed commitment and restored energy I thought I had found on vacation. I imagine that the return to the classroom, the shop, the office, the lab, feels much the same. What was that thing I was going to do? What was that change I was going to make? What was my resolution? When is my next vacation? I wonder too, if we don’t approach worship in much the same way. I hope that your time here in this place or the time you spend with us online is a source of renewal, of inspiration. I hope you find in this time together a sense of connection to God and to neighbor. I hope you remember who you are and whose you are and take with you the resolve to live a life of devotion and discipleship. But I also wonder if that inspiration, renewal, and devotion is harder to remember in the harsher reality of overflowing inboxes, looming deadlines, impatient clients, and traffic jams. It makes me wonder too if John the Baptist ever questioned his work. I wonder if he ever found it difficult to remember what drove him into the wilderness. I wonder if he questioned his message, his method, standing for hours in the murky waters of the Jordon, in wet camel hair with wrinkly toes and a belly full of locusts, baptizing repentant strangers. I can imagine his hope for the messiah had as much to do with finding some rest for himself as some rescue for his people. We hear echoes of his hope in his question, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” I need you, Jesus. I need a messiah to come and fix all this. I need a rescuer to come and save us from Rome, from ourselves. I need to be reminded that this work is not in vain, that this work is accomplishing something larger than me. I need to know that my sacrifice is seen, is valued, is effective. I need to be baptized by you. Why do you need to be baptized? Theologians, pastors, preachers, and parishioners have been repeating John’s question since he asked it. If this Jesus is God why does he come for a baptism of repentance? Of what does Jesus need to repent? But I think this is the wrong question. The church has spent some 20 centuries defining, articulating, and proclaiming one baptism for the forgiveness of sin. We speak of a rite of initiation, of inclusion. Paul speaks of our old selves being buried with Christ and raised with him to new life. We speak so much and so often of what baptism is and does that we haven’t seen the forest for the trees. Baptism is a rite on initiation. Baptism does forgive our sins. Baptism does unite us to Christ. But this day to remember the Baptism of Jesus, set here in this season inaugurated by the Feast of the Epiphany, invites us to see something less familiar to us in the rite of baptism. This season after Epiphany is about encountering the mystery of incarnation, about contemplating the union of God and matter, the manifestation of God with us in the person of Jesus, the Christ. Baptism is about more than initiation or inclusion, forgiveness or religious identity. Our baptism is the beginning of a new way of showing up in the world, a new way of seeing and encountering the world. Jesus was baptized by John in the Jordon to give us the gift of baptism, a sacred mystery that reveals the sacred mystery at the heart of the universe— the whole of creation is a sacrament. The whole world is a sacrament, the union of matter and God’s very self. And in this sacramental universe we are each priests, ministers of word and work. No matter your vocation, no matter your occupation, you are the steward of a sacred mystery in which God transforms your work into a means of grace. Your scrubs, lab coat, uniform; your nametag, backpack, briefcase; your sport coat, pants suit, apron are all sacred vestments. Your desk, work bench, hospital bed; your countertop, stovetop, laptop; your changing table, kitchen table, conference table; each are a sacred altar where you pour out yourself as an offering and receive back nourishment in return. We do not come to worship, to the font or the altar, to find this sacred mystery in the only place that it exists. We come to worship, to the font and the altar, to learn to see this sacred mystery everywhere that it exists. We should learn from these sacraments to see that God in Christ, revealed in the humble majesty of his birth, proclaimed from heaven in his baptism, is not a singularity in the story of the cosmos, but a particularity which exposes the deeper truth. The incarnation is not limited to Jesus. The incarnation is exposed in Jesus. This is the Epiphany, the revelation of God in Christ, after which we begin to see the God in all things. The whole cosmos is filled with God. All creation emanates from God’s very being, and is destined to return to this source. This is what we mean by salvation. Baptism is the proclamation that this human, this sinner, this mortal, is also divine, a saint, immortal. Creation is filled with the life and love of God. Your life is filled with the life and love of God. Your work is an extension of this Creation, and your work too is filled with the life and love of God. We, like John the Baptist, encounter the Christ in every patient, client, customer; in every student, parent, volunteer; in every spouse, child, neighbor. We, like John, must approach our work as a sacred honor, a humble privilege of service to God’s very self. This does not mean that Mondays won’t suck, that customers won’t complain, that inboxes won’t overwhelm us, that babies won’t cry, that we won’t get sick and tired of standing in our private Jordons wishing to be rescued. It will mean that we begin to see the sacrifice as unto God, as part of a larger sacred mystery as a holy privilege of humble service in a world overflowing with the life and love of God. Amen.

Like most folks, I suspect, I love Christmas carols. They stick in my head Long after the tree is gone, And the lights are put away. I would dare say that most of us could even sing the first verses of most Christmas carols by heart. 100% off-book. Think about it, “Joy to the World,” “Silent Night,” “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” “The First Noel,” “It Came upon a Midnight Clear.” But the real meat of these carols is in the second, or even third verse. Take for instance, “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” We could all sing Yet in thy dark streets shineth The everlasting light, The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight. But do we pray O holy Child of Mary Descend to us, we pray. Cast out our sin And enter in, Be born in us today? The birth of this Christ child is not some abstract theological concept with no bearing on our reality. Nor is this baby the object of mere sentimentality. This child’s birth is good news to shepherds Working the third shift And living in a field To whom It came upon a midnight clear, That glorious song of old… “Peace on the earth, Good will to all, From heaven’s all gracious king.” But you don’t have to work the third shift to identify with the next verse: And you, beneath life’s crushing load, Whose forms are bending low, Who toil along the climbing way With painful steps and slow; Look now, for glad and golden hours come swiftly on the wing; oh, rest beside the weary road and hear the angels sing. And in this child, whom the herald angels sing we, Veiled in flesh the Godhead see! Hail, incarnate Deity!... Mild he lays his glory by, Born that we no more may die, Born to raise each child of earth Born to give them second birth. Our hope is that this God veiled in flesh This incarnate deity Is Emmanuel. God with us. God for us. The God of shepherds Who lays his glory by To shine in dark streets, Pleased as a man with us to dwell. Epiphany is the second verse of Christmas. Epiphany is where the story gets complicated. Epiphany is where we realize just how vulnerable God is in the form of a baby, in early first century Palestine, under the reign of a murderous tyrant, bent on keeping power at all costs. The epiphany is that God is vulnerable because God is love. In this Love incarnate, we find that grace is the very nature of the Universe, because grace is the word we use to describe the way love behaves toward the beloved. This is the mystery we heard about in Ephesians, the light we heard about in Isaiah, and the guiding star of those wise men. Christ Jesus, God in the flesh, Love in a body, revealed to the whole world. Many of us could sing O holy night, The stars are brightly shining, It is the night of our dear Savior’s birth. As we go from here, Into a world divided, awash in pain, and on the brink of war We must remember that Truly he taught us to love one another, His law is love and his gospel is peace Chains shall he break, For the slave is our brother, And in his name, All oppression shall cease. His law is love and his gospel is peace! As the songs of angels cease, as the babe in the manger becomes the toddler on Mary’s knee, as the wise men take another road home, we begin to live into the second verse of the incarnation. The verse that tells us that the Almighty is also the all-vulnerable. That God has come among us, to live and love, to suffer and die alongside us. To live and love to suffer and die, not instead of us but in us, and through us. God’s radical solidarity with the whole of creation in Jesus Christ is the Epiphany. And this radical solidarity is the calling of the whole church. Where there is pain, where there is suffering, where there is oppression, we are sent not only to proclaim good news but to embody the law of love and the gospel of peace. May the Epiphany continue in each of us! Amen.