Advent 2, Year A, December 7, 2025

Of all the Christmas cards I’ve ever seen,

I have never seen one

featuring a wild-eyed desert mystic

wearing animal skins,

honey in his beard and a bug leg stuck in his teeth,

yelling,

“You brood of vipers!!”

It’s the second Sunday of Advent.

If you’ve been around for Advent before,

you may have braced yourself for John the Baptist -

an apocalyptic street preacher

whose “good news” sound more like a dire warning.

Maybe he missed the

“Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem” part

of Isaiah’s prophetic poetry.

The curmudgeonly prophet raises his voice

and lets us have it:

"You brood of vipers!

Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?

Bear fruits worthy of repentance."

If you’re looking for a soft, comfortable entry

into the season before Christmas,

John is not your guy.

There’s nothing “lowly and mild” about child of promise.

The Gospel of Matthew

makes a point of telling us that

John both appears and cries out in the wilderness,

in a landscape that is desolate and barren.

Why the wilderness?

Why the lonely desert for our Advent reflections?

Well, if you have any experience with real estate,

you know the mantra: “Location location location.”

Location is key.

The place where we stand,

the terrain we occupy,

the space from which we speak —

these things matter.

While it’s unlikely you’ve ever seen John the Baptist

featured in an Advent calendar

or on a Christmas greeting card,

all four Gospels place him

front and center in Jesus’s origin story.

John’s austerity is the only gateway

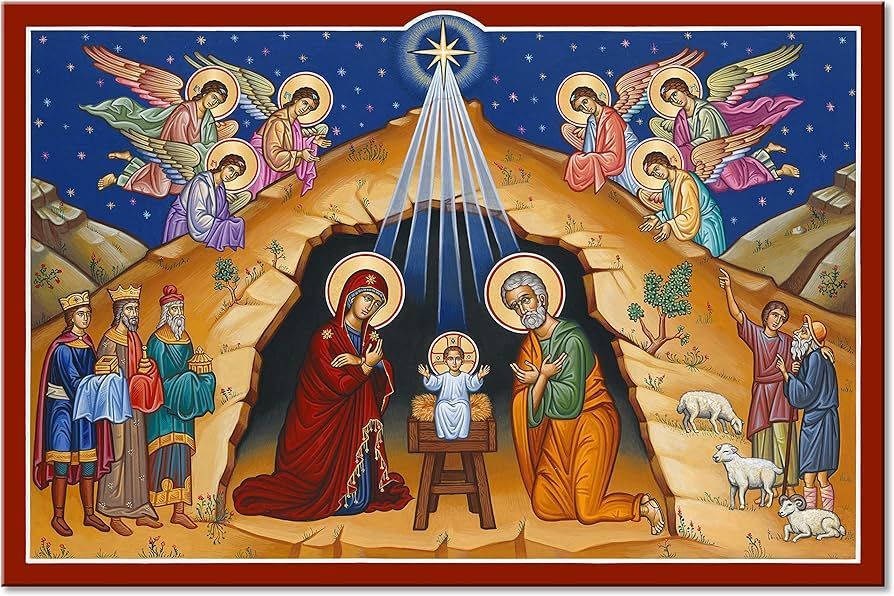

we have to the swaddling clothes,

angel's wings, and fleecy lambs

we hold dear each December.

And as baffling as it may seem,

the holy drama of the season

depends on the disheveled baptizer’s opening act.

But why the wilderness?

Wouldn’t John be more successful

yelling in the center of town -

at the gate of the emperor?

Well, let’s look at the scene

Matthew is setting.

John comes from the wilderness to the Jordan.

The crowds,

including the Pharisees and Sadducees,

come from Roman occupied Judea,

from civilization.

On one side of the river is the wilderness,

a place of vulnerability, risk, and powerlessness.

In the wilderness, there is no safety net,

no Plan B, no rainy-day savings account, no quick fix,

and no 24hr grocery store,

which means if all you can find to eat

are locusts and wild honey,

you’re having sweet grasshoppers for dinner.

In the wilderness, life is raw and unsettled,

and illusions of self-sufficiency shatter very quickly.

On the other side of the river

is Judea,

Jerusalem,

and imperial oppression.

When these city folk come to the river,

they find themselves

on the outskirts of the peace through strength

offered by Rome.

It is a place where the soft neediness of our common humanity

is exposed.

In the wilderness, people have no choice

but to wait and watch

as if their lives depend on God showing up,

because quite frankly, they do.

It is into this environment so far removed from safety,

an environment so formless, so void

that the Word of God speaks,

and what we learn about ourselves in this environment

will be as hard to swallow

as honeyed insects.

John cries from the wilderness,

“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near!”

Crowds stream out of the cities and towns,

out of the jurisdictions of Herod and Caesar,

out of the promised land

to its threshold.

This river,

the wilderness on one side

and the land of milk and honey on the other,

is the way to freedom.

Slaves and wanderers waded in

and the redeemed people

of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob

walked out.

John now calls this redeemed people back,

back to the wilderness,

back to the doorway,

back to the waters of salvation.

Repentance is the path of return,

to meet the wander in the waters

and to walk out redeemed.

These words,

“sin” and “repentance”

are quite loaded,

even avoided in modern Christian circles.

If you, like me, grew up in a fundamentalist circle,

the word “sin” and its association with

shame, guilt, and condemnation

likely bring a good amount of discomfort.

Many of us also distrust the word of scripture

because we've seen how easily

it can be manipulated to justify

one moralistic agenda over another.

Yet Advent begins

with an honest, wilderness-style reckoning with sin

and we can’t get to the manger

unless we go through John the Baptist,

and John is all about repentance.

Does all this talk of wilderness

and repentance

mean there is no room for comfort

at all?

If we’re able to get past being triggered by John’s words

to follow him out into the wilderness,

perhaps what we’ll find is comfort -

comfort in the fact that

something more profound is at stake

in our souls than

personal moral failure

and private reconciliation.

Perhaps what ails us is something

deeper, grimmer, and far more consequential.

Growing up, I was taught that

sin was "breaking God's laws,"

"missing the mark,"

"committing immoral acts," or

“anything that separated me from God.”

These definitions aren't wrong.

They’re just incomplete.

They don’t go far enough.

They don't name the fullness of all we struggle with.

Sin, at its heart,

is a broken relationship to reality itself.

It's anything that interferes with

the opening up of our whole hearts

to God, to others, to creation, to our very selves.

Sin is estrangement, disconnection, disharmony.

It's the sludge that slows us down,

that says, "Quit. Stop trying.

Give up. Change is impossible.

I’m not responsible for my actions.

You’re not my problem."

In other words, sin is apathy, care-less-ness,

the frightened resistance to an engaged life.

It is the opposite of creativity,

the opposite of abundance,

the opposite of flourishing.

Sin is a walking death.

And it is easier

to spot, name, and confess a walking death

in the wilderness

than anywhere else.

We have to be confronted

before we can be comforted.

This is why John underscores

his message of repentance

with a harrowing description

of the coming Messiah:

"He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.

His winnowing fork is in his hand,

and he will clear his threshing floor

and gather the wheat into the granary;

but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire."

If you weren’t squirming before,

I bet you are now.

How in the world is this good news,

this portrait of a Jesus

with pitchfork and fire

who judges, sorts, and burns?

In Malachi 3,

the Lord says,

“I will draw near to judge you.”

Often, we equate judgment with condemnation.

But what if God was saying

“I will draw near

so I can see you better.”

What if John is saying

that the coming Messiah

really sees us?

That he knows us at our very core?

That the winnowing fork

is an instrument of deep love,

patiently wielded by One

who wants to separate from us

all the dried-up husk

that we once used to protect the precious seed within?

Perhaps then,

it's in offering God every piece of our lives

that we give God permission to "clear" us —

to separate all that's no longer useful

from all that is good, beautiful, and worthy.

John calls us to return,

to come back to the water,

to the threshold,

to re-enter civilization,

no longer a slave or a wanderer,

but as citizens, neighbors,

in a promised society.

God calls us to the water

to make peace

by making justice,

with God,

within ourselves,

among each other.

When this happens,

the wilderness and our lives,

become a place where we can see

the landscape as a whole

and participate in God’s great work

of leveling inequality and oppression.

“Prepare the way of the Lord,” John cries,

quoting the prophet Isaiah.

“Make his paths straight.”

We prepare for the coming of Jesus

by becoming accountable individuals

within a just society.

We are called by our baptism

to accountability and responsibility

for the way of the world.

Accountability and responsibility make justice.

Justice makes peace.

Peace prepares the way to a better world.

Amen.