Advent 3, Year A, December 14, 2025

I grew up singing in church.

I didn’t grow up a Lutheran,

and so, the hymnody I learned

was not the baroque melodies

and ancient chants of the early

and medieval church,

but the old timey,

shaped note,

and bluegrass tunes

of early 20th century Appalachia.

When I was growing up,

the church choir

sounded more like the Grand Ol’ Opry

than a grand old opera.

There was no pipe organ,

only a piano,

and a reluctant pianist,

who was more talented than confident.

There were a few different choir directors

in my time there.

This position was usually filled

like the pianist’s position;

whoever could say “no” least convincingly

ended up with the task.

It was pick-up choir.

We didn’t rehearse,

and everyone who wanted to

was invited to join us from the congregation.

It was often a 50/50

or 60/40 split

between choir and congregation.

It was in this church singing

that I was introduced to the Spirituals.

Songs like “Were You There?”

“Sweet Little Jesus Boy,”

and “Sweet, Sweet Spirit.”

These songs moved me

in ways that the other old-timey music we sang

never did.

Singing in church

turned into singing in school,

where I learned more Spirituals,

like “Elijah Rock,”

“Soon I Will Be Done”

and a cadre of Spirituals

arranged and composed by Jester Hairston.

In his autobiography,

Fredrick Douglass writes about his experience

as a slave in Maryland

before his escape.

Douglass writes about the songs the slaves sang.

He writes:

“[These songs] told the tale of woe

which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep;

they breathed the prayer and complaint

of souls boiling over

with the bitterest anguish.

Every tone

was a testimony against slavery

and a prayer to God

for deliverance from chains. …

I have been utterly astonished,

since I came to the North,

to find persons

who could speak of the singing among slaves

as evidence of their contentment and happiness.

It is impossible

to conceive of a greater mistake.

Slaves sing most

when they are most unhappy.

The songs of the slave

represent the sorrows of his heart;

and he is relieved by them,

only as an aching heart

is relieved by its tears.”

This as all made me wonder,

What should we make of Mary’s singing?

How should we hear Mary’s words?

What tune was her heart singing that day?

Would her happy words

be set in a minor key,

or in ecstatic exaltation

to make the Hallelujah Chorus

sound like a radio jingle?

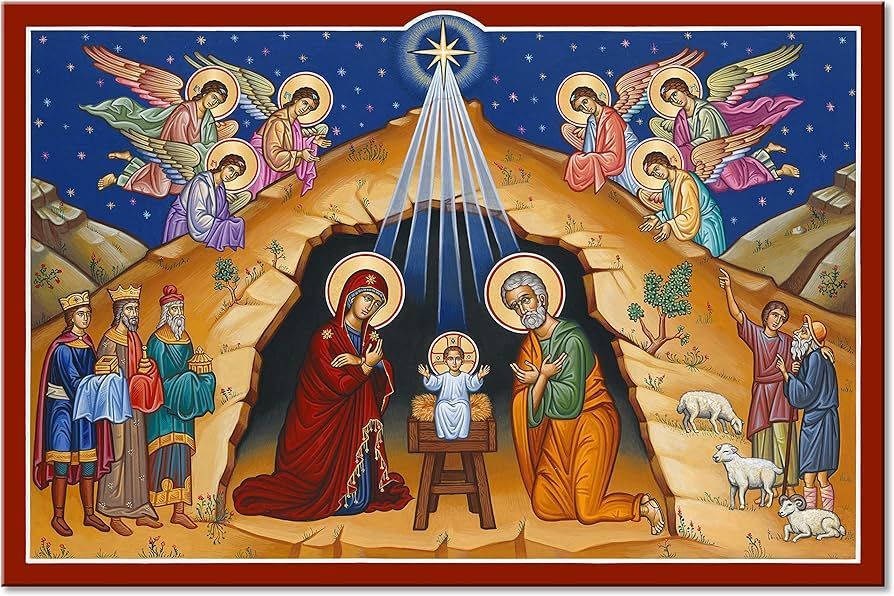

Our gospel reading today

is a song

that Luke’s Gospel tells us

arises from the heart

of a young girl,

visited by an angel,

pregnant before her arranged marriage,

sent away to live in secret

with her distant cousins,

in a land occupied by a foreign power.

When she arrives at her hiding place,

her secret is known,

even by the baby in her cousin’s womb.

Mark Lowery’s

“Mary Did You Know?”

is a sweet song,

but the better question is,

Mary, did you cry?

Did you stress eat?

Did you doubt?

Were you afraid?

Were you embarrassed?

Did you hold the hand

and wipe the brow of Elizabeth

as she gave birth to John?

Did this terrify you?

How did you bear the weight

of being “blessed” for “all generations?”

Were your hands raised to the sky

as your soul magnified the Lord,

or did your tears wash the dust from your face?

As Douglass reminds us,

spontaneous singing

ought not deceive us into believing

that the joy of Mary’s song

was somehow proof

that Mary’s ankles didn’t swell,

that her back didn’t hurt,

that she didn’t have morning sickness

or weird cravings,

or that this child

now “with child”

wasn’t overwhelmed

by the enormous weight

of all that she knew.

Mary sang to remember;

to remember the promises of God,

to remember the promises of the angel,

to remember the faithfulness of God,

the goodness of God,

the mercy and justice of God.

Mary sang to remind us,

of God’s promises,

and faithfulness,

and goodness,

and mercy,

and justice.

Mary sang to remind God.

Mary sang to

“breathe the prayer and complaint

of bitter souls boiling over in anguish….

a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.”

A prayer to God

to scatter the proud in the thoughts of their hearts,

and to scatter proud thoughts in her own heart.

A prayer to God

to bring down the mighty and raise up the lowly,

and to make sure she was one of the lowly ones.

A prayer to God

to fill the hungry with good things

and send the rich away empty,

and to trust that what filled her now

was indeed a good thing.

Mary sang for joy,

a joy born of anguish transformed,

sorrow transcended,

suffering transmuted.

Mary’s song did not spring from her joy.

Mary’s joy sprang from her song.

Beloved,

Mary’s song

is a form of prayer

we have long neglected.

Mary’s song

arose from her willingness

to embrace the reality that was.

Mary’s song,

and the songs of slaves

were not weak resignation

to the suffering of the moment

as God’s divine, inscrutable plan,

but blessed assurance

in the nearness of a God who suffered with them,

the steadfastness of a God who would deliver them,

the justice of a God who would vindicate them,

and the power of a God

who transforms pain into comfort,

sorrow into solace,

suffering into relief,

and death into resurrection.

Mary’s pondering of the angel’s greeting

and treasuring the truth in her heart

reconciled her to the harsh reality of the world

as it is,

and grew in her

the hope of the world to come.

When we allow these songs to rise up in us,

to well up in our hearts,

and minds,

and mouths

we too have joined Mary’s song,

the song of hope for slaves,

the oppressed,

the hungry,

the lowly.

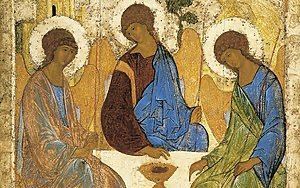

We have become the mother of God,

bearing life and hope and salvation

into the world

by our song,

by our prayer,

by our joy.

Amen.